US Japan Philippines Trilateral Spotlights Minilateral Challenge

New summit sectoral inroads reinforce delivery imperative. Plus rising "Cold War connectors"; new cyber strategy; China rail links; trade shop launch & more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to the latest edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! If you haven’t already, you can upgrade to a paid subscription for $5 a month/$50 a year below to receive full posts by inserting your email address and then selecting an annual or monthly option. You can visit this page for more on pricing for institutions, groups as well as discounts. For current paid subscribers, please make sure you’re hitting the “view entire message” prompt if it comes up at the end of a post to see the full version.

For this iteration of ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief, we are looking at:

Assessing the geopolitical and geoeconomic significance of the first-ever Japan-Philippines-U.S. trilateral summit and the inroads and implications to watch moving forward;

Mapping of regional developments, including a new strategic partnership and the largest cited global airdrop;

Charting evolving geopolitical, geoeconomic and security trends such as the role of non-aligned “Cold War connectors”; a new cyber strategy and a trade shop launch;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments and quantitative indicators including new China connectivity chatter; digital crackdown fallout and big energy market shift;

And much more! ICYMI, check out our review of a new book on China’s assertive diplomacy in Southeast Asia and beyond from earlier this week.

This Week’s WonkCount: 2,197 words (~ 10 minutes)

New Strategic Partnership; Largest Global Airdrop; Civil War Spillover & More

Rising Cold War Connectors; Countering Coercion & Growing Complexities in Asia’s Growth Story

“Different from the early years of the Cold War, a set of nonaligned ‘connector’ countries are rapidly gaining importance and serving as a bridge between blocs,” notes a new working paper released by the International Monetary Fund on changing global linkages amid talk of a “new Cold War.” The paper notes that these connectors, including Vietnam, have gained more in China export shares (see graphic below) and likely brought resilience to global trade and activity. That said, they may not necessarily be increasing diversification, strengthening supply chains or lessening strategic dependence (link).

Figures Assessing Connector Country Emergence Now vs. the Cold War

“Washington must closely monitor the situation and take steps to help protect the sovereignty of Southeast Asian nations from PRC intimidation and territorial encroachment,” argues a new paper released by the Center for a New American Security on China’s gray zone activity in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean region. The paper suggests a number of recommendations, including enlisting minilaterals like AUKUS and the Quad as well as investing more in regional architecture (link).

Map of Select China Port-Related Developments Around the Indian Ocean Region

“Amid these three major secular trends, the ASEAN+3 region’s growth landscape has never been more complex,” concludes a new report from the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) with coverage of Southeast Asian economies alongside China, Japan and South Korea. The report identifies aging, trade reconfiguration as well as technological change as these three major trends, arguing that the region’s long-term growth prospects will be premised on its ability to navigate risks and opportunities therein (link).

Three Major Cited Secular Trends for the ASEAN+3 Growth Landscape

US Japan Philippines Trilateral Summit Spotlights Minilateral Focus

What’s Behind It

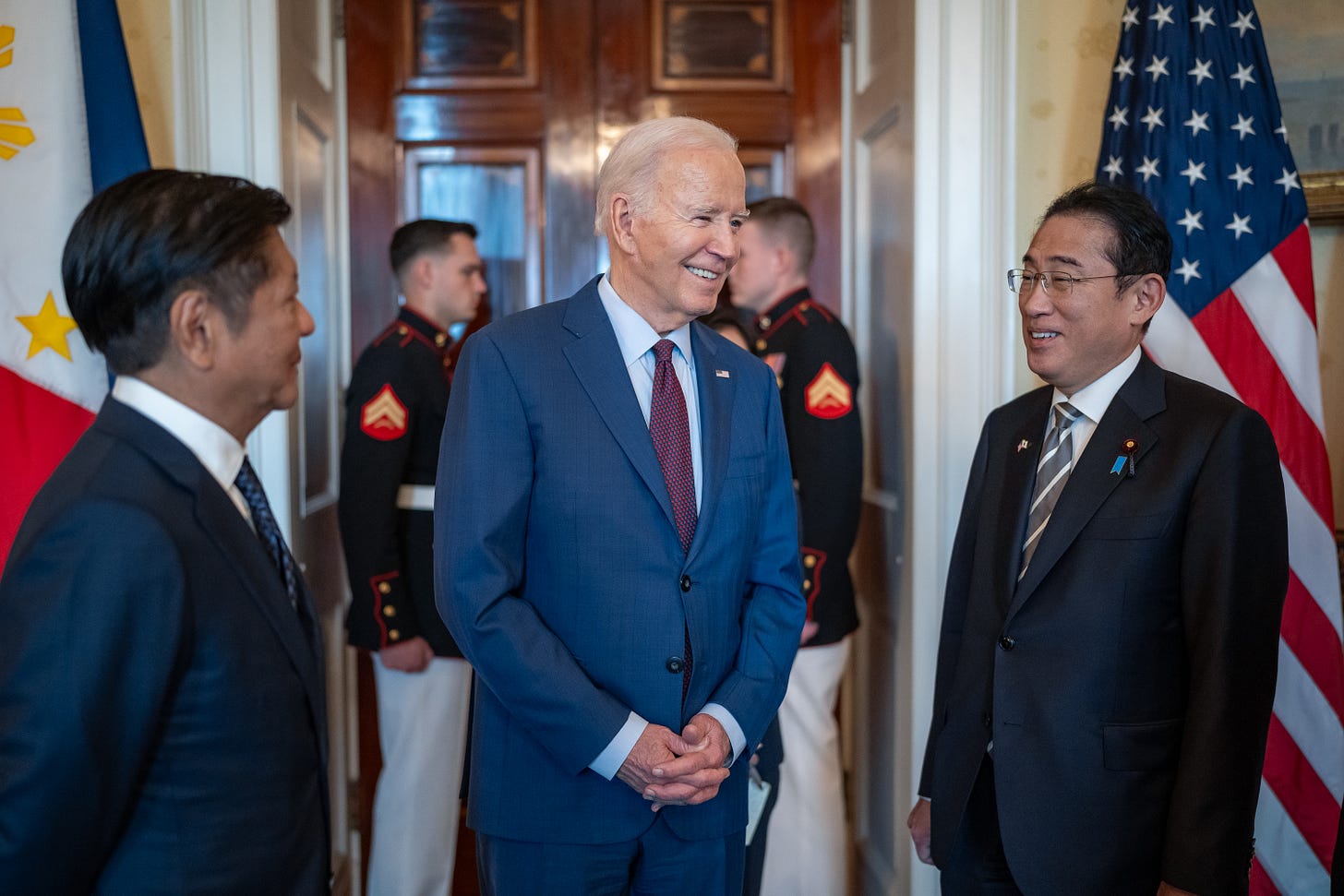

Japan, the Philippines and the United States announced new inroads in the first-ever trilateral summit between the three countries on April 11, including new drills and initiatives in strategic security and economic sectors1. The move caps nearly a year of senior-level trilateral engagements amid growing ties between the three countries, quad activities with Australia and Manila’s own growing security partnerships with like-minded countries amid China’s continued assertiveness in the South China Sea (see timeline snapshot below)." “[T]his meeting can be just a beginning,” Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said in opening remarks when the leaders and their teams met at the White House2.

Select Recent Developments Related to the U.S.-Japan-Philippines Trilateral Summit

The summit offers an example of intensified Indo-Pacific minilateral networking underway, including in Southeast Asia. The focus is often on security aspects of U.S.-driven minilaterals like AUKUS. In truth, more countries are seeking new flexible arrangements with and without Washington beyond the security realm to address challenges that include and extend beyond China3. Notable past non-U.S. examples include the Australia-India-Japan trilateral and the expanding Digital Economy Partnership Agreement initially grouping Singapore, Chile and New Zealand4. Within Southeast Asia, caricatured multilateral-minilateral duels between ASEAN and AUKUS miss proliferating minilaterals in the region itself. These include the evolving Australia-India-Indonesia trilateral as Indonesia gets a new president and China’s Lancang-Mekong Cooperation framework. Beijing is also building its own institutions while downplaying Washington’s inroads as evidence of its narrow alliance focus relative to China’s inclusive approach. Ahead of the summit, Beijing played up visits from Southeast Asian officials including from East Timor, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam to intensify perceptions of Manila as an outlier5.

Why It Matters

The trilateral underscores the U.S. minilateral management challenge. Washington has made some institutional inroads in recent years, including multilateralizing Garuda Shield drills with Indonesia, setting up the Mekong-US partnership amid shifting realities and adding Singapore to a handful of close tech partners6. But Washington’s true challenge is resourcing and sustaining these minilaterals to become more comprehensive in addressing partner needs beyond the China challenge. The United States also remains disconnected from key parts of the regional economic minilateral architecture after its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (since rebranded CPTPP), despite efforts like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework7. China is also not standing still. While U.S. officials believe these minilaterals may isolate China, Beijing is trying to construct its own partnerships, slow U.S. efforts through coercion and counternarratives as well as shape institutions including by trying to join CPTPP and DEPA8.

The summit highlighted areas to watch in trilateral cooperation as well as the U.S.-Philippine alliance in the coming weeks and months9 (see the table below on areas of note and what will be key to watch, followed by more insights on “Why It Matters” and “Where It’s Headed”. Paid subscribers can read on as usual to our other regular weekly newsletter sections that offer additional insights including a dashboard of industry developments and analysis of notable quantitative metrics useful for practitioners, scholars and watchers).