Southeast Asia's Giant Scam Challenge in the Mekong Spotlight

Plus coming partnership upgrade; fresh defense pact; China's Belt and Road; new cross-continental FTA & much more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to this edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! For this iteration, we are looking at:

Assessing the significance of recent restrictions tied to Southeast Asia’s giant proliferating scam networks and impacts on the wider region and world (Note to Readers: ASEAN Wonk is on the ground this month in several mainland Southeast Asian countries and border regions for a couple of separate projects. In addition to regular coverage, we will include snapshots of shareable findings where they tie in with developments, with the scam networks being a case in point).

Mapping of regional developments including a coming partnership upgrade; heightened terror fears and a new defense agreement;

Charting evolving trends such as on Southeast Asian responses to China’s Belt and Road, climate performance amid COP28 global climate change talks and related issues;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments including a new cross-continental FTA; fresh climate inroads; the expanding cross-border payment landscape and more;

And much more!

WonkCount: 1,812 words (~9 minutes reading time)

Coming Partnership Upgrade; Heightened Terror Fears; New Defense Agreement & More

Southeast Asia's Giant Scam Challenge in the Mekong Spotlight

What’s Behind It

The US, UK and Canada imposed coordinated restrictions on December 8 that included giant scam networks proliferating across the Mekong subregion. The restrictions came ahead of the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on December 101.

The development was just the latest spotlighting the sprawling scam networks that have affected nearly all Southeast Asian countries and dozens of nations beyond the region as well. Though these scam networks are at times described as shadowy networks in the Mekong subregion, those who have witnessed their manifestations firsthand know that this belies the practical reality that their inner workings have long been known and their reach has increasingly gone global2. When ASEAN Wonk was most recently in the vicinity of the notorious Golden Triangle earlier this month at the crossroads of some of this activity, one official detailed the density of transactions in the backdrop of ongoing construction across the Mekong, pausing periodically to gesture with his fingers during points where money was exchanged amid corruption and negligence3. Ongoing developments over the past few years, including China’s growing economic influence, the COVID-19 pandemic and Myanmar’s 2021 coup have also contributed to shifts in how transnational criminal networks operate4.

Why It Matters

The restrictions are the latest manifestation of growing regional and international awareness of the need to crack down on these scam networks. Regionally, though these networks are far from new, they have gotten much more publicity over the past few years. Southeast Asian officials from nearly every country have had to contend with evacuations of citizens or extradition of suspects over the past year, with concerns expressed behind closed doors at ASEAN meetings and a statement adopted by the grouping as well5. Internationally, several organizations including the United Nations have disclosed the scale of these networks, which involve links to practically six of the world’s main continents; hundreds of thousands of people across Southeast Asia; and billions of dollars in annual revenue6. The intersection of these dynamics with other trends and developments, including China’s influence in Southeast Asia and the ongoing Myanmar civil war, has also partly resulted in greater traction, even though this at times risks conflating disparate challenges and drawing attention away from granular local realities.

Newly Sanctioned Entities Related to Southeast Asia’s Scam Networks

Practically speaking, the restrictions largely reinforce those already in place for entities related to well-known scam network hubs. The UK government did highlight the significance of this issue, with the scam-related restrictions listed first in its publicized statement and covering nearly a third of them (14 out of 46)7. At the same time, most of the entities mentioned are quite familiar to those who track this space (see table above). The entities essentially map on to three scam network hubs across three countries— the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone in Laos; Shwe Kokko in Myanmar; and various areas in Cambodia including Sihanoukville8. Five of the 14 were sanctioned collectively by the US Treasury back in 2018 part of what was then already collectively termed the Zhao Wei Transnational Criminal Organization9. Notably, the newly listed entities also include not just companies and businessmen, but also members of the Myanmar Border Guard Force which have previously been linked to these scam networks.

What Lies Ahead

Looking ahead, part of the scrutiny will be on the extent to which we could see more of an international response to what has become a global challenge. Though sanctions are one tool in a policy toolkit, the global comprehensive nature of the scam network challenge demands a coordinated, comprehensive response (see one visual depiction of the global network below)10. Some of the components are already in play, be it promoting more global public awareness and quiet intergovernmental cooperation in areas like extradition of suspects and cross-border repatriation of victims. But there is much more to be done across the board — from better data-sharing to fostering collaboration between government and non-governmental stakeholders whose advocacy is a critical part of the equation11. Officials also privately note that cross-border cooperation can also leverage elements of national responses already being mulled in some Southeast Asian countries, such as the setting up of national scam response centers and media campaigns12.

Visual Depiction of the Global Reach of Southeast Asia’s Scam Networks

Apart from the international response, the evolution of these scam networks themselves and their contextual dynamics will also be a critical variable. A chief strength of these networks is their ability to adjust and pivot as states shift their responses, and this will continue to be the case in the coming months. There are also some stubborn realities that are likely to persist. One is that though Myanmar is a key hub for these networks and a necessary part of a broader set of conversations on the subject, the country’s ongoing internal strife means its status is unlikely to meaningfully change anytime soon13. Another is that as much as these networks are partly about China’s economic influence, they are also at times taking place in an enabling environment in mainland Southeast Asian states with issues such as corruption and capacity, some of which is linked to prominent elites and influencers. That makes actually addressing root causes much more difficult than the rhetoric suggests.

Perceptions of China’s Belt and Road; Tracking Climate Performance amid COP28 & Shrinking Civic Space

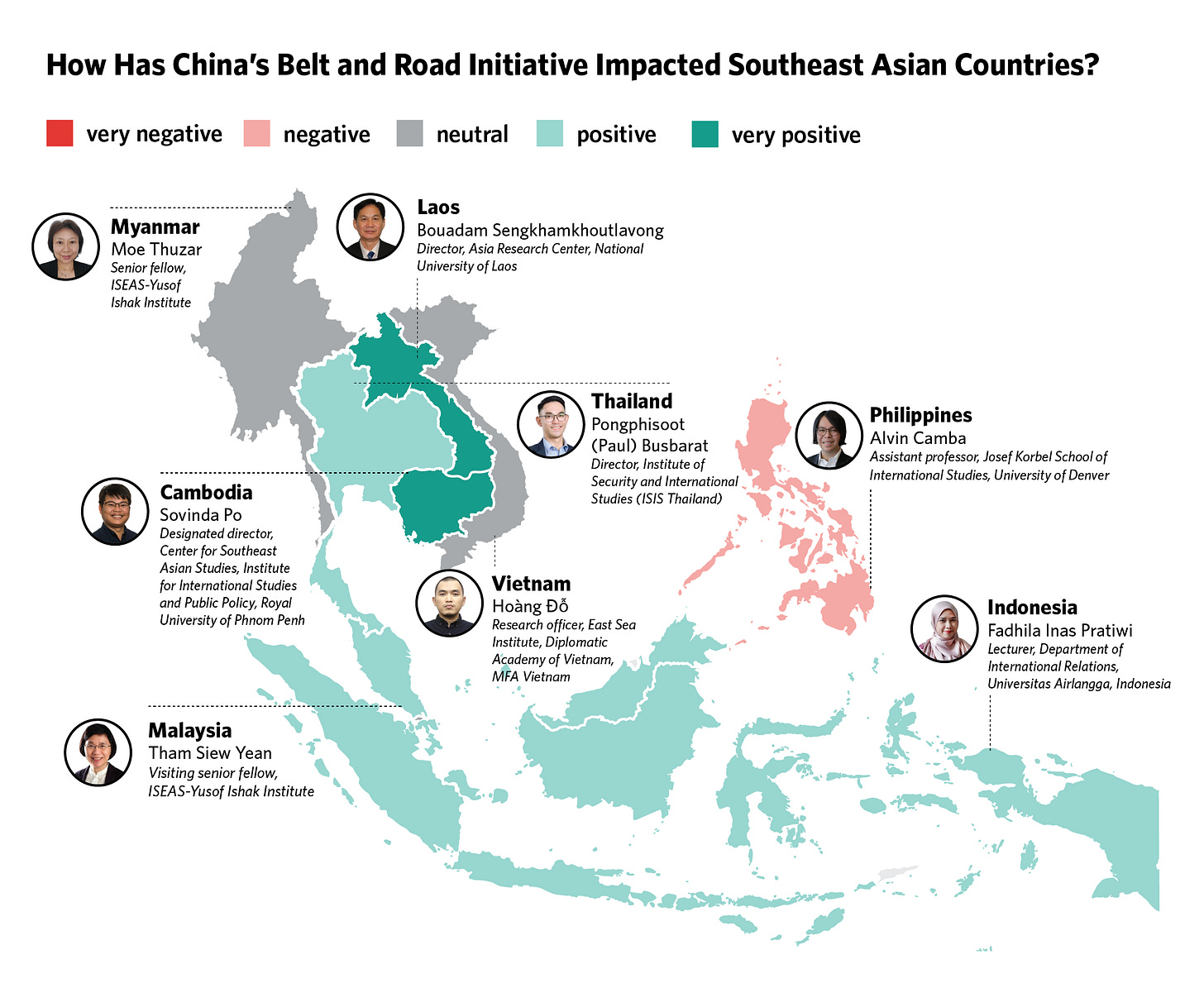

“Scholars from eight Southeast Asian countries provide their takes on the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in their countries for the past decade,” notes the introduction of a new regional pulse check published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The scholars choose from among five levels of impact: very positive, positive, neutral, negative, or very negative (link).

Select Perceptions of China’s Belt and Road in Southeast Asian Countries

“Indonesia falls 10 places to rank 36th in this year’s CCPI, with an overall low rating,” notes the latest iteration of the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) released in conjunction with COP28 international climate change talks in Dubai. On the positive side of the ledger, Thailand and Vietnam both register big jumps of 17 and 13 places respectively. The Philippines (climbing by 6 spots) and Malaysia (dropping by 3 places) round out the five Southeast Asian states featured in the index (link).

Climate Change Performance Index 2024 Select Ratings Table

“There has been some progress in Asia and the Pacific, as the upgrading of Timor-Leste from obstructed to narrowed shows,” observes a new CIVICUS report on civic space. The report has five categories within which countries are places — red (closed); orange (repressed); yellow (obstructed); light green (narrowed); and dark green (open). Dili was the only case of an upgrade within Southeast Asia. (link).