Indonesia Foreign Policy After 2024 Elections: Beyond US-China Hype

From artificial intelligence to critical minerals, a deep dive into geopolitical and geoeconomic dynamics that could shape up after Indonesia's 2024 elections.

Dear Readers - today, ASEAN Wonk is pleased to launch our latest product called “DrillDown,” which offers granular, deep-dive conversations with practitioners on policy developments in Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Our objective here is to drill down, sieve out and deliver insights from those who have firsthand experience with the policy questions we wrestle with. Our first iteration below looks at how Indonesian presidential elections could affect the country’s geopolitical and geoeconomic trajectory — including and beyond the lens of U.S.-China competition.

If you have not already, do consider subscribing below by inserting your email address and then selecting a monthly or annual option. And if you have already done so, do consider forwarding this to others who may be interested. Thank you for your support as always!

WonkCount: 2,701 words (~13 minutes reading time).

Indonesia Foreign Policy After 2024 Elections: Beyond US-China Hype

Indonesia still arguably does not receive the attention it deserves for its own sake given its weight as the world’s fourth-largest country; third largest democracy; largest Muslim-majority country; Southeast Asia’s largest economy by size; and the region’s only permanent member of the Group of Twenty (G-20). Yet Indonesia has featured prominently as part of broader storylines in 2024, not least because it is among the leading countries on the long list of holding elections, with polls kicking off February 14. We at ASEAN Wonk have been closely tracking the foreign and security implications both in our on work as well as that of others. Those implications extend far beyond U.S.-China competition, even though some in the U.S. policy bureaucracy also view Jakarta as a so-called “swing state” in U.S.-China competition and U.S.-Indonesia ties were elevated to a comprehensive strategic partnership last year (see our take here on the complications in that “swing state” narrative, and some of the lingering gaps between rhetoric and reality despite progress made).

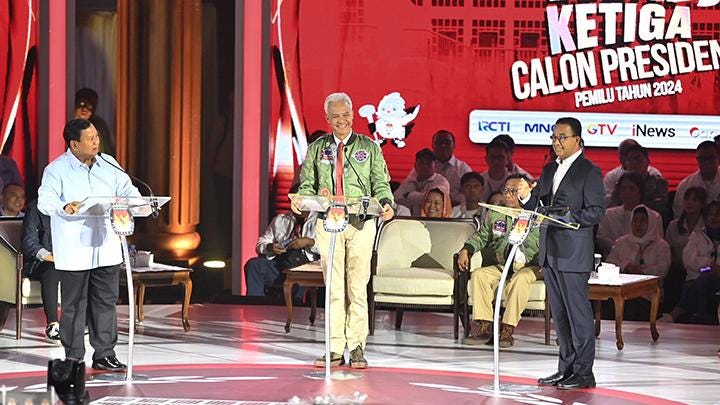

To drill down on these dynamics and more, ASEAN Wonk spoke to Ambassador Robert Blake, who was the former U.S. ambassador to Indonesia (2009-2013) and played a key role in initiatives such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership in 2022 as the former senior advisor to U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry. After over three decades in a range of governmental leadership positions, Ambassador Blake is currently, among other things, the co-chair of the U.S.-Indonesia Society, which just hosted granular discussions engaging with the teams of all three presidential candidates. The wide-ranging “DrillDown” below touches on several areas, including future scenarios that governments and companies should be prepared for; Indonesia’s geoeconomic and geopolitical opportunities and challenges; and sectoral areas to watch including critical minerals, energy and the digital economy.

ASEAN Wonk: The elevation of the U.S.-Indonesia relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) a few months ago was one of a series of inroads we’ve seen the Biden administration make in Southeast Asia, which include the double upgrade with Vietnam, a new tech partnership with Singapore and new defense traction in the U.S.-Philippine alliance and broader minilateral networking. How would you frame the importance of that U.S.-Indonesia CSP elevation for our readers, both for the bilateral relationship given Indonesia’s own strategic importance, and also wider U.S. Southeast Asia policy given the realities of U.S.-China competition?

Ambassador Blake: Indonesia is the largest Muslim-majority democracy in the world. It boasts the largest economy of ASEAN and one that will continue to grow in importance for the foreseeable future because of Indonesia’s relatively young population and its recent success diversifying its economy to become one of the fastest growing digital economies in the world, and a player of growing importance in green supply chains. President Jokowi focused his presidency on domestic issues such as improving Indonesia’s infrastructure and the economic diversification noted above, although bilateral cooperation on key regional issues such as Myanmar intensified in Jokowi’s second term.

ASEAN Wonk: The U.S.-Indonesia relationship is operating in a geopolitical and geoeconomic context which some have called a polycrisis or “compound crisis”, including the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Gaza conflict following the COVID-19 pandemic and rising U.S.-China competition. Some of these dynamics have exposed tensions in the way the United States and Indonesia look at some global issues. We have also seen periodic moments where that has been in the spotlight, including Indonesia flirting with joining the BRICS as it also moves forward with an OECD bid. How would you frame the way in which this broader geopolitical and geoeconomic context creates both areas of convergence and divergence for U.S.-Indonesia ties, and what is your assessment of how both sides are navigating this context?

Ambassador Blake: As the United States and China compete for influence in Southeast Asia and beyond, Indonesia is seen as being one of a handful of large swing states – along with countries like Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and India – who will have an important geopolitical influence globally if they choose to exercise it. Indonesia senses this opportunity as it competed successfully for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council in 2019-2020; kept its seat on the UN Human Rights Council; and organized humanitarian airlifts of assistance to Turkey after its earthquake and to Gaza, to name just a few examples. Indonesia’s interest in the OECD is a welcome development, given global backsliding on democratic freedoms and the importance of sustaining market reforms in Indonesia. The rationale for joining BRICS is less clear given the many divisions among BRICS countries which make consensus decisions more difficult.

ASEAN Wonk: Indonesia just wrapped up its term as the holder of the annually-rotating ASEAN chairmanship in December. Indonesia’s chair year witnessed inroads in some areas of geoeconomic and geopolitical interest to the United States, including trying to shore up the maritime agenda within the bloc and connecting the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific to sectoral areas such as infrastructure. How would you assess Indonesia’s ASEAN chairmanship year in terms of the opportunities it opens for U.S.-Indonesia and wider U.S.-Southeast Asia cooperation? And were there any challenges that stood out that both Washington and Jakarta should keep in mind in 2024?

Ambassador Blake: In some ways, Indonesia’s ASEAN chairmanship marked a positive year for U.S.-ASEAN relations. I attended the launch in Washington of the U.S.-ASEAN Center, which will help multiply government, private sector, educational and other contacts which is important since awareness of ASEAN in Washington remains low, despite our strong trade and investment ties as detailed by the great ASEAN Matters publication. The United States is also scaling up the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment in Southeast Asia to provide a high-standard, transparent alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Despite considerable efforts by Indonesia’s foreign ministry, progress on geopolitical challenges continued to be hampered by internal ASEAN structural issues that make building a consensus on hard-hitting initiatives on tough issues like Myanmar difficult to muster.

ASEAN Wonk: The three presidential campaigns have been laying out their approaches to areas of domestic and foreign policy ahead of the upcoming Indonesian elections. What strikes you as some of the areas of continuity and change, particularly on foreign policy and views with respect to the United States as a former ambassador? And as someone who engages regularly with the business community, what are you seeing in terms of how firms are preparing for different scenarios?