BRICS Expansion and Southeast Asia: What’s Behind Indonesia’s Balancing Act?

Plus a new Quad first; giant scam networks; big defense deals & much more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to this edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! For this iteration, we are looking at:

Assessing Indonesia’s non-inclusion in the list of a new and rare BRICS expansion wave at a recent summit meeting in South Africa;

Mapping of regional developments including a first quad exercise of its kind involving the Philippines and a coming upgrade in Vietnam-Australia relations;

Charting evolving trends such as Southeast Asia’s giant Mekong scam networks and the receptiveness to AUKUS in Southeast Asia;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments including new Indonesia defense deals and Southeast Asia’s expanding cross-border payments landscape;

And much more!

A New Quad First for the Philippines; Coming Vietnam-Australia Upgrade; New Thai-Cambodian Leader Connect & More

BRICS Expansion and Southeast Asia: What’s Behind Indonesia’s Balancing Act?

Indonesia’s lack of inclusion in a rare BRICS expansion spotlighted Jakarta’s calibration of economic and geopolitical imperatives under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s foreign policy approach in the face of broader regional and global challenges.

What’s Behind It

Indonesia was not included on the list of new BRICS members despite earlier speculation that it would be part of a new and rare expansion wave. Jokowi said the country would “conduct a thorough study and calculation” before submitting an official expression of interest, unlike the six countries that joined the grouping — Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia1. Indonesian officials had also clarified earlier that Jokowi’s attendance ought not to be conflated with a decision on membership2. Jakarta’s approach was closely watched as part of a broader story of expansion of the BRICS — a group of emerging economies comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Though initial hopes for the BRICS may have been rooted in its economic potential, it has increasingly come to be seen as a grouping advocating a geopolitical outlook that is distinct from the Western-dominated Group of Seven (G-7) countries, particularly in the face of developments such as intensifying U.S.-China competition and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Indonesia’s engagement at the BRICS highlighted its utilization of diplomatic institutions to advance Jokowi’s priorities, as seen in fora such as G-20 and ASEAN. Jokowi’s office emphasized the portion of his remarks on economic issues he is fond of raising, such as addressing instances of perceived trade discrimination like EU palm oil restrictions or supporting commodity downstreaming evident in Indonesia’s nickel export ban (see table below)3. He also predictably avoided touching directly on broader geopolitical issues such as U.S.-China tensions, though he did call for consistent respect for international law and human rights and make general references to the “spirit of Bandung” dating back to when Indonesia hosted the Bandung Conference of non-aligned countries in 1955. This pattern of calibrating between the imperatives of economic growth and geopolitical management has also been at play in Indonesia’s ASEAN chairmanship, as noted previously in these pages. It was also a trend we saw when Indonesia chaired the G-20 last year4. ASEAN Wonk understands from sources familiar with the aforementioned dynamics that though there had been initial traction in Jakarta’s BRICS interest, evolving realities and interventions partly accounted for what was perceived as a punt on this front rather than a sense that this would be ruled out indefinitely.

Topics Raised by Jokowi at the BRICS Summit and Domestic Priority Relevance for Indonesia

Why It Matters

Indonesia’s BRICS approach spotlighted the tension between geopolitical and economic imperatives in its foreign policy approach under Jokowi. Jokowi has sought to use Indonesia’s voice in regional and global institutions to amplify his domestic-centric, economic-focused foreign policy vision, secure support for a more equal, inclusive and multipolar world as well as insulate Indonesia from geopolitical tensions. Yet at the same time, his administration has found that these very geopolitical tensions have made it more challenging for Indonesia to expand economic opportunities without inviting scrutiny on the country’s broader foreign policy positions and strategic outlook. That tension is evident despite Indonesia’s status as the world’s fourth-most populous country, third-largest democracy and largest Muslim-majority nation.

The benefits of Indonesia formally joining BRICS are far from clear, even if Jakarta intends to further reinforce its efforts at foreign policy and economic diversification. BRICS membership could give Indonesia another forum to advocate for a more multipolar world and strengthen economic ties. Yet Indonesia’s status is such that Jakarta is already on a long list of a diverse array of institutions, three of which it has been chairing recently — ASEAN (2023), the G-20 (2022), and MIKTA with Mexico, Korea, Turkey and Australia (since March). Indonesia has also been able to exercise leadership in other fora during Jokowi’s tenure, including via a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council 2019-2021 and as chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association in 2015-2017. Jakarta arguably also has the heft to develop ties with individual BRICS countries — already with Indonesia in the G-20, albeit in a different context — and other key states on its own without the geopolitical baggage of BRICS membership. Indeed, some of the global headlines missed the fact that the BRICS meeting was only part of Jokowi’s first-ever, four-country visit to Africa which also included Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania. In all three countries, in addition to economic deals, he pushed for more trade and investment following Mozambique’s status as Indonesia’s first preferential trade pact partner in Africa5.

Where It’s Headed

Indonesia’s calibration between its quest to join the league of more developed countries while building support among developing countries will continue to be a theme to watch. For all the focus on the BRICS, the bigger picture is that Indonesia continues to concurrently engage in institutions with emerging economies while also aspiring to be in the league of more developed countries as part of Jokowi’s vision to make it one of the top five economies by 2045. A case in point is Indonesia’s bid to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which has received less attention relative to the BRICS membership question. Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi also captured this balance in her remarks at the BRICS meeting in June, when she said that her message about economic injustice was the same one that Jokowi had delivered to the G-7 meeting hosted by Japan in Hiroshima earlier this year. There, Jokowi had even suggested forming a new body of commodity exporters akin to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

More broadly, the extent to which this could shift in post-Jokowi Indonesia is also an interesting question as Indonesia heads into elections set for February 2024. Jokowi’s largely domestic-centered, economic-focused foreign policy vision has seen Indonesia stick to advocating a transactional approach narrowly tied to its interests at a time when broader challenges are proliferating across the Indo-Pacific and the world. Yet Jakarta’s approach could recalibrate under a more ideological or geopolitically-focused leader or if it experiences a major foreign policy crisis that triggers rethinking.

Unpacking Southeast Asia’s Giant Mekong Scam Networks; AUKUS, Southeast Asia and the Philippines’ Role; Indonesia’s Nickel Policy Debate

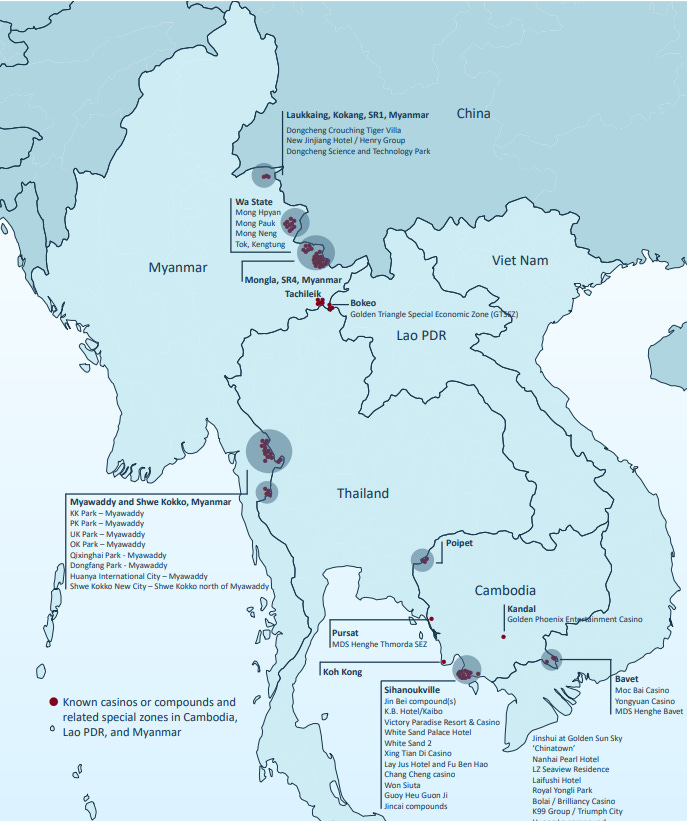

“International NGOs and other agencies have identified over 40 nationalities of trafficking victims in scam compounds in Southeast Asia,” notes a new summary policy brief published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime on the giant scam networks across the region centered in the Mekong subregion (see map below). The brief includes several policy recommendations, including the creation of a centralized Southeast Asia database for data storage and sharing as well as the creation of local level MoUs and SOPs to enable swift cross-border victim rescues (link).

Locations of Casinos or Reported/Raids Scam Compounds in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar

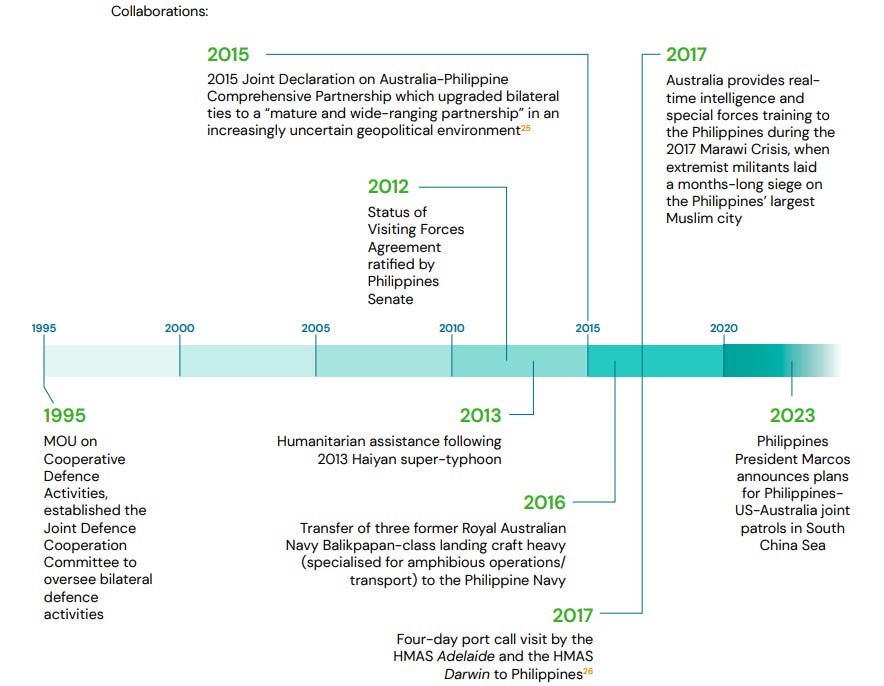

“The Philippines sees expanded cooperation with AUKUS member countries — including an AUKUS+1 — as a primary means of ensuring Indo-Pacific stability into the future,” notes a new commentary published as part of the Perth USAsia Centre’s AUKUS series (link). The piece situates AUKUS within the wider security cooperation the Philippines has been cultivating with individual partners within AUKUS including Australia (see a visualization of select defense collaboration below).

Brief Timeline with Select Recent Developments in Australia-Philippines Defense Collaboration

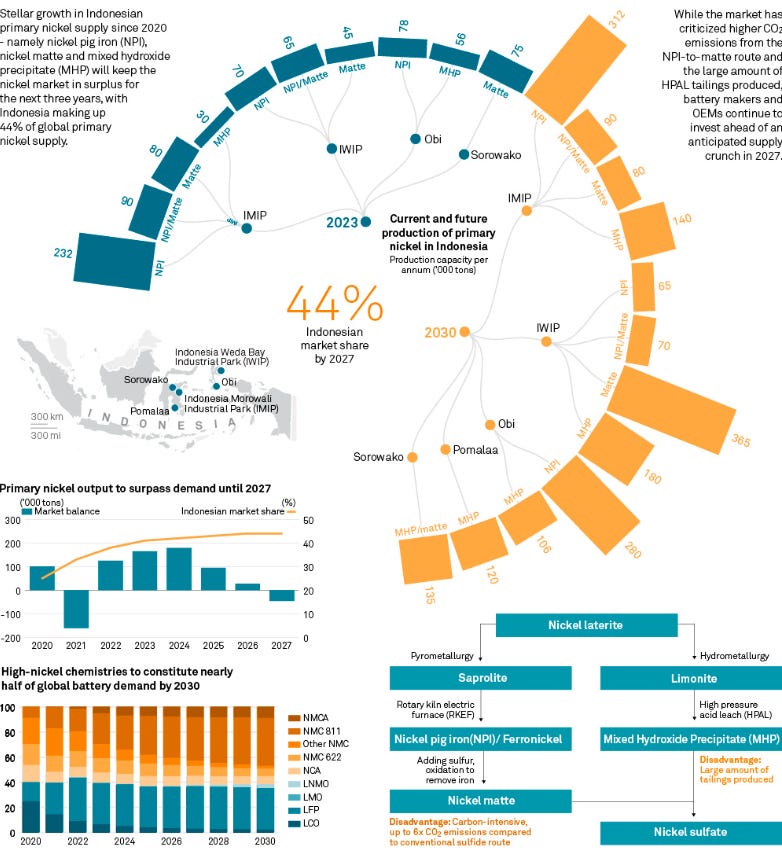

“President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s policy to develop the country’s mineral downstream industry, especially for nickel, is once again facing scrutiny,” notes an article over at The Jakarta Post. The policy continues to generate debate both inside and outside Indonesia about its costs and benefits, links with China’s influence in the country and the growing global scrutiny on critical minerals (link) (see graphic below from S&P Global)6.