What's Behind Indonesia’s Russia-Ukraine Peace Initiative?

Beyond the headlines the proposal has generated, it is a reminder of the broader dynamics behind Jakarta's evolving approach and the diversity of views between and within countries.

WonkCount: 1,993 words (about 10 minutes).

Over the weekend, Indonesia’s Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto made headlines when he suggested a new peace plan for ending the Russia-Ukraine war which drew quick criticism from some western security officials. Though Prabowo himself is no stranger to voicing his views on major geopolitical issues, it nonetheless put Indonesia’s approach to the Russia-Ukraine war in the headlines amid continued attention to the conflict’s trajectory, the spectrum of evolving regional and global views and Jakarta’s own shifting domestic political dynamics.

Background

Indonesia has traditionally sought to play a so-called “free and active” (bebas-aktif) role in world affairs, and its foreign policy has witnessed its share of shifts over the decades in line with changes in domestic politics and the regional and international environment – whether it be the deposing of President Sukarno in 1967 which saw a recalibration of what had been close ties with the Soviet Union, or restrictions following rights abuses in East Timor in 1999 that for some in Jakarta exposed the limits of dependence on western countries. Though current President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has consistently portrayed himself as a primarily domestic- and economic-centered leader since assuming office in 2014 with only a selective interest in foreign policy, Indonesia has not been immune from global headwinds and geopolitical challenges, including COVID-19 and a more assertive China and Russia — indeed, in the case of the latter, for instance, Indonesia eventually decided against buying Russian fighter jets in 2021 in the shadow of potential U.S. sanctions.

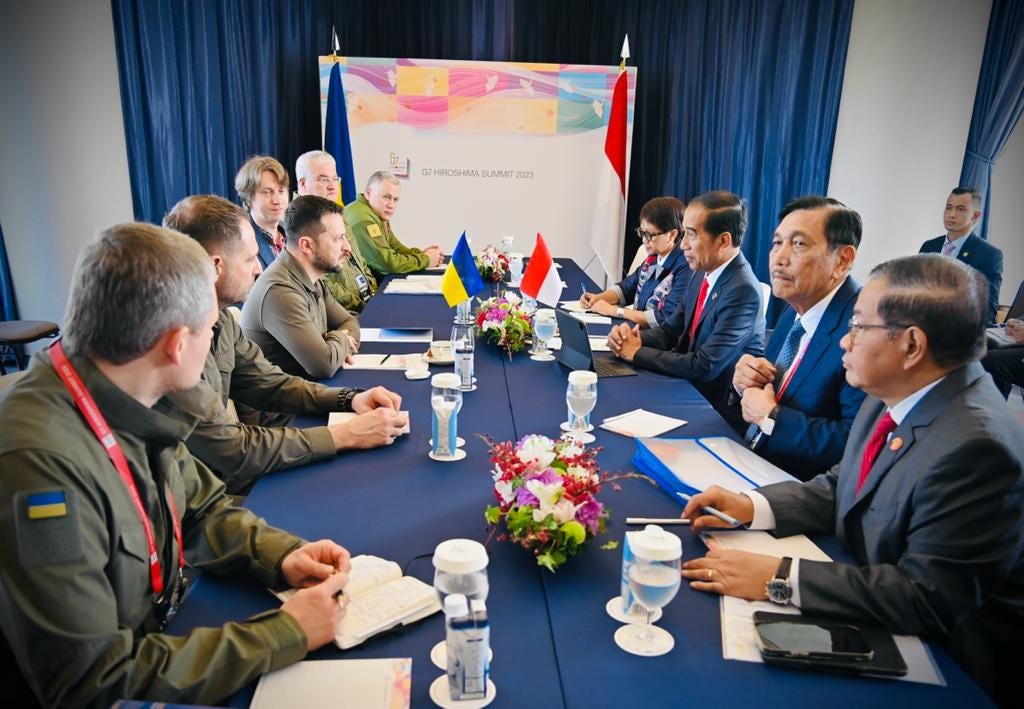

Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, Indonesia’s evolving approach has repeatedly found itself in the headlines. Indonesia’s initially vague references to Russian culpability in its public response when the war broke out in February put scrutiny on links to Moscow in areas like defense and pockets of pro-Russian public sentiment within the Indonesian media environment, even though since then, within Southeast Asia itself, Jakarta has been among those that have voted in favor of UN General Assembly resolutions condemning Russian aggression (see also our recent take on Vietnam’s evolving approach in regional context). In June, Jokowi made headlines when he became the first Asian leader to visit both Russia and Ukraine, though the trip itself did not yield major breakthroughs and came largely in the context of particularly high domestic stakes for Indonesia at the time with its first-ever chairing of the Group of Twenty (G-20) and concerns about food security, including wheat imports. Nonetheless, in 2023 thus far, apart from Indonesia’s responsibilities as the chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Jokowi has continued to mention Indonesia as a potential “bridge for peace,” as he did when he met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on the sidelines of the Group of Seven (G-7) summit in Japan last month. This has come amid several other developments along the way, such as the conclusion of an extradition agreement with Russia and requests from Bali’s governor to amend visa policies with cases of misbehavior and crimes committed largely by Russians.

Beyond the evolution of Indonesia’s overall approach to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Prabowo, who does not typically shy away from chiming in on major geopolitical issues, has not been afraid to speak out himself on this matter. For instance, last November, he went through a list of initial lessons that could learned from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and then clarified that he was neither being pro-Russia nor pro-Ukraine and was merely focusing on the substance at hand. And at last year’s iteration of the Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) annual defense conference in Singapore, when asked about the applicability of Indonesia’s free and active foreign policy in the wake of contemporary challenges which include Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he noted that in the context of various countries that Indonesia had ties with, “we also remember that Russia has also helped Indonesia at the time of the Soviet Union” and also quoted Nelson Mandela who once observed that “one of the mistakes that the outside world makes is to think that their enemies should be our enemies.” His recalling of past ties to Russia is not unique to Indonesia and can be seen in other cases in the region as well such as India and Vietnam. And while Prabowo’s is among one of several perspectives within Indonesia, it is worth noting that in terms of public opinion metrics like favorability ratings towards Russia, Indonesia has typically appeared closer to where India and Vietnam are than to Singapore or South Korea, with the caveat that the ongoing war itself could shift perceptions over time (see graphic below as an example).

Graphic on Indonesia’s Favorability Towards Russia in Relative Regional Perspective (Direction of Travel Between 2022 and 2023 in Democracy Perceptions Index)

Significance

Yet Prabowo’s floating of a peace plan is the first time we have seen an explicit initiative of its kind publicly unveiled by an Indonesian official in a high-profile setting with accompanying specifics. In his speech, Prabowo floated a proposal which included the cessation of hostilities in place; withdrawal by both sides of 15 kilometers each from forward positions to a new demilitarized zone; the formation of a United Nations monitoring and observer force to be immediately set up and deployed along this demilitarized zone; and the carrying out of a referendum in “disputed territories” to ascertain the wishes of majority of the inhabitants in various areas. Prabowo also declared that Indonesia was “prepared to contribute military observers and military units under the peacekeeping auspices of the United Nations,” and in his speech and in subsequent responses to questions, cited the need to put the war in perspective relative to other conflicts like Korea and Vietnam, as well as invasions experienced by countries in other parts of the world including the Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

That the speech itself attracted so much attention comes as little surprise, even though the contours of Indonesia’s overall position on the Russia-Ukraine war have not fundamentally shifted. To be sure, much of this has to do with its substance, with seems to suggest an equivalence between Moscow and Kyiv and portrays parts of Ukrainian territory as disputed (Prabowo, for his part, clarified in the Q & A session that, in his view, Indonesia’s voting record at the UN should dispel any sense of equivalence, and the objective of his speech was to go past the issues of righteousness and responsibility and get down to concrete proposals for conflict resolution). More broadly, apart from being the defense minister of Indonesia – traditionally regarded as a leader in Southeast Asia and is also the world’s fourth most populous country and third largest democracy – Prabowo, as he himself said at the SLD, is seen as being among the leading contenders for Indonesia’s presidential elections which are set to take place in February 2024, with the politicking already well underway. Furthermore, Prabowo’s proposal, like Singapore’s willingness to impose unilateral sanctions on Russia, is a rare example of a bold foray on this issue in Southeast Asia, where much of the region is preoccupied by a confluence of other major internal and external challenges. Indeed, it bears noting that in spite of the controversial specifics of Prabowo’s proposal that raised eyebrows, his speech also rooted this in an acceptance of the connection between Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic security that not everyone in the region necessarily shares to the same degree.

Beyond Southeast Asia itself, this also comes in the context of peace proposals coming from so-called Global South countries over the past few weeks and lingering concerns among some countries including the United States that it could grow increasingly challenging to keep up the international pressure on Moscow should the war continue to drag on. This included the suggestion of a peace mission by African leaders to both Zelenskyy and Russian President Vladimir Putin, and a G-20-like peace bloc by Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva that would incorporate major developing countries which was overshadowed by a supposed G-7 meeting with Zelenskyy that did not take place. Irrespective of the content of these proposals and their likelihood of success, they point to a tug of war between the quest for clarity by Ukraine and its most ardent advocates around the world regarding culpability for the war and continued support on the one hand, and a murkier set of realities noted by some key governments of developing countries, including a more pressing need to confront economic realities which they are bearing more of the brunt of relatively speaking given developmental levels; the relative attention that the war is getting relative to other conflicts; and even in some cases obfuscation on the issue of responsibility.