Malacca Straits Killer Hype Masks Thailand’s Land Bridge Risks

Plus Vietnam-Cambodia-Laos trilateral defense ties; ASEAN-Australia ties; large new gas discovery and much more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to this edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! A note that ASEAN Wonk will be off next week for the end of the year - we will be back starting January 2. Happy holidays to all and thank you for your support! And if you haven’t already, do consider a paid subscription to help support our work.

For this iteration, we are looking at:

Assessing the hyped effects on the Malacca Straits from Thailand’s land bridge project touted by premier Srettha Thavisin at the ASEAN-Japan summit;

Mapping of regional developments including the Vietnam-Cambodia-Laos trilateral border defense exchange and potential China-Philippines talks amid continued South China Sea tensions;

Charting evolving trends such as on the evolution of ASEAN-Australia relations and semiconductor policy;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments including a large new gas discovery; a big aircraft purchase acceptance; a coming minimum wage rise and more;

And much more! ICYMI: check out our analysis of the outcomes of the recent ASEAN-Japan commemorative summit.

WonkCount: 1,914 words (~9 minutes reading time)

Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Trilateral Defense Ties; China-Philippines “Jaw-Jaw” & More

Malacca Strait Killer Hype Masks Thailand’s Land Bridge Risks

What’s Behind It

Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin led a roadshow event to promote Thailand’s land bridge project to Japanese investors in Tokyo on the sidelines of the ASEAN-Japan summit, as he has done at other fora including APEC. The project aims to provide a new trade route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans within Southeast Asia’s maritime consciousness – in addition to the current Malacca Straits running through Malaysia and Singapore – by linking two deep sea ports on Thailand’s eastern and western coasts via a rail and road system1. The current Thai government estimates that the 90-kilometer connection, costing around one trillion baht ($28 billion), could reduce travel time by around four days and decrease shipping expenses by 15 percent relative to the Straits of Malacca2.

The event was just the latest in a push by Srettha to drum up attention to the project, with visions that trace back centuries. The land bridge idea is far from new, and related ideas like a canal across the Kra Isthmus go back to at least to the 17th century, with various analyses about the winners and losers under different scenarios3. The idea of land bridges being used instead of canals in certain contexts is not unheard of in other regions, with a case in point being the Panama Canal (though in that case, it would shave thousands of miles of voyage rather than hundreds of miles)4. Yet a sea of concerns had previously prevented Thai governments from pursuing this course, including the trillion baht price tag, negative environmental fallout, rough mountainous terrain and security concerns in Thailand’s restive south. These issues still exist today. Nonetheless, Srettha has devoted consistent, high-profile international attention to it since taking office. ASEAN Wonk understands he has even rejigged some of his meetings to prioritize this and other economic initiatives rather than some other wider interactions suggested by those around him at key international engagements5.

Why It Matters

The project’s connection to the Malacca Straits means it holds wider regional implications that will be carefully watched. The Malacca Straits has offered the shortest sea route linking Southeast Asia to India, the Middle East and the wider world, accounting for by one count nearly half of the world’s total annual seaborne trade tonnage and the majority of Asia’s oil imports6. But Srettha has argued that alternatives are needed given that maritime traffic growth would outstrip its capacity by 2030 (see the table below for some key future signposts the government has highlighted). This has predictably generated hype because of potential reduction in traffic in the Straits of Malacca. In reality, such doomsday predictions are quite premature. Even if a land bridge were to be built, much of the tangible economic effects would be rooted in the calculus for actors on route choices. As of now, basic questions remain unanswered, including the extent to which any time gained through a shorter route via a land bridge would be offset by the inefficiencies in unloading and reloading cargos to move across it7.

Key Future Signposts Mentioned for Thailand’s Potential Land Bridge

It is also critical to Srettha’s advancing of his own legacy while in office. Srettha, a businessman before assuming the premiership, has consistently championed the notion of proactive economic diplomacy to boost Thailand’s growth and raise its profile on the international stage. This comes as Thailand, Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy, has seen its economic performance lagging most of its neighbors in recent years and some questionable deals as the intra-ASEAN race intensifies for post-pandemic growth and sectoral advantages in areas like electric vehicles. In this context, the land bridge has been connected to broader objectives such as turning Thailand into a high-income nation and creating a southern economic corridor to connect the Gulf of Thailand and Andaman Sea. This is despite doubts about its exact benefits. The current government claims the project would create 280,000 new jobs and help boost Thailand’s growth by 5.5 percent8.

Where It’s Headed

Looking ahead, scrutiny is likely to continue on the extent to which Thailand is able to secure concrete investments and manage other challenges. Thus far, though the government has pointed to general interest, practitioners know that is very different from companies actually formally agreeing to contribute tangible funding for the project. The project has gone through cabinet approval in October, but it is still subject to other litmus tests including feasibility studies and environmental impact assessments. Even if there is traction, construction would be a multi-decade endeavor. This creates inbuilt uncertainty, especially given the ebbs and flows of Thai politics with multiple maneuvers, coups and constitutional changes. Indeed, it is difficult to have a conversation with Thai interlocutors on longer-term questions such as this without also getting into shorter-term political uncertainties, including Srettha’s future amid potential changes in internal politics within Pheu Thai, the role of Thaksin Shinawatra’s family and the monarchy.

More broadly, there will also be a focus on the ongoing shipping state of play in the Malacca Straits. The issues being used to back up the case for the land bridge, such as congestion, security and rising shipping volume and costs in the Straits of Malacca, are not new. But episodic concerns, such as the uptick in piracy in the 2000s or the opening of new ports, have also been utilized by various constituencies to inject more momentum for changes either with respect to the Malacca Straits or in affected countries like Malaysia, such as instituting new security patrols or increasing the competitiveness of port infrastructure and supply chain connectivity. Changes in the wider environment will also play into any movement on the land bridge. Indeed, more realistic versions of the land bridge see it less as an alternative to the Straits of Malacca per se, but as another option that could handle a small portion of the tonnage (less than a quarter by the Thai government’s recent estimate) through two ports.

ASEAN-Australia Ties; Resentment in Indonesian Elections & Semiconductor Policy in Malaysia

“For too long the economies of ASEAN have not been central to Australia’s economic thinking,” Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese noted when delivering the 2023 Lowy Lecture at Australia’s Lowy Institute. He added that Australia is in the process of upgrading its economic strategy for Southeast Asia, and that this would be a priority when the country hosts the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit set for March 2024 (link).

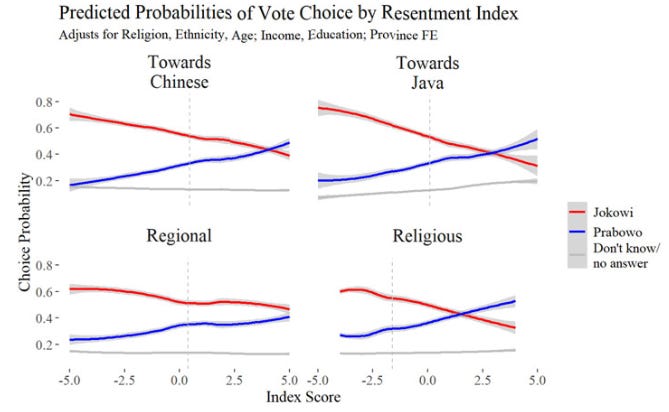

“Across all four measures, higher resentment was associated with greater probability of supporting Prabowo in the 2019 presidential election,” notes a new article over at New Mandala. The piece, which is a summary of a longer publication with the Journal of East Asian Studies, focuses on resentments related to Chinese-Indonesian and non-Muslim minorities; Java; and urban–rural divides (link).

“Beyond treating the semiconductor industry as an investment, Malaysia should gradually build up stronger policy leadership,” notes an op-ed in the East Asia Forum by Malaysia’s Deputy Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry Liew Chin Tong. The piece addresses several areas where more investments are necessary, including paying its skilled workers better and strengthening STEM education and technical and vocational training to prepare a more robust talent pipeline (link).