Assessing ASEAN's New Military Drill: How the 2023 Solidarity Exercise in Natuna Matters

Plus new Philippine South China Sea legal case sequel talk; a new China-East Timor partnership; new Huawei Southeast Asia training hub chatter and much more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to this edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! For this iteration, we are looking at:

Assessing the implications of the new ASEAN military drill and broader effects on the regional grouping;

Mapping of regional developments including Philippine South China Sea legal case sequel talk; new China-East Timor partnership and more;

Charting evolving trends such as on U.S.-China competition and Southeast Asian perceptions of climate change as well as related issues;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments including a new Huawei Southeast Asia training hub chatter; prospects of Vietnam’s unicorn companies and more;

And much more!

WonkCount: 1,465 words (~7 minutes reading time)

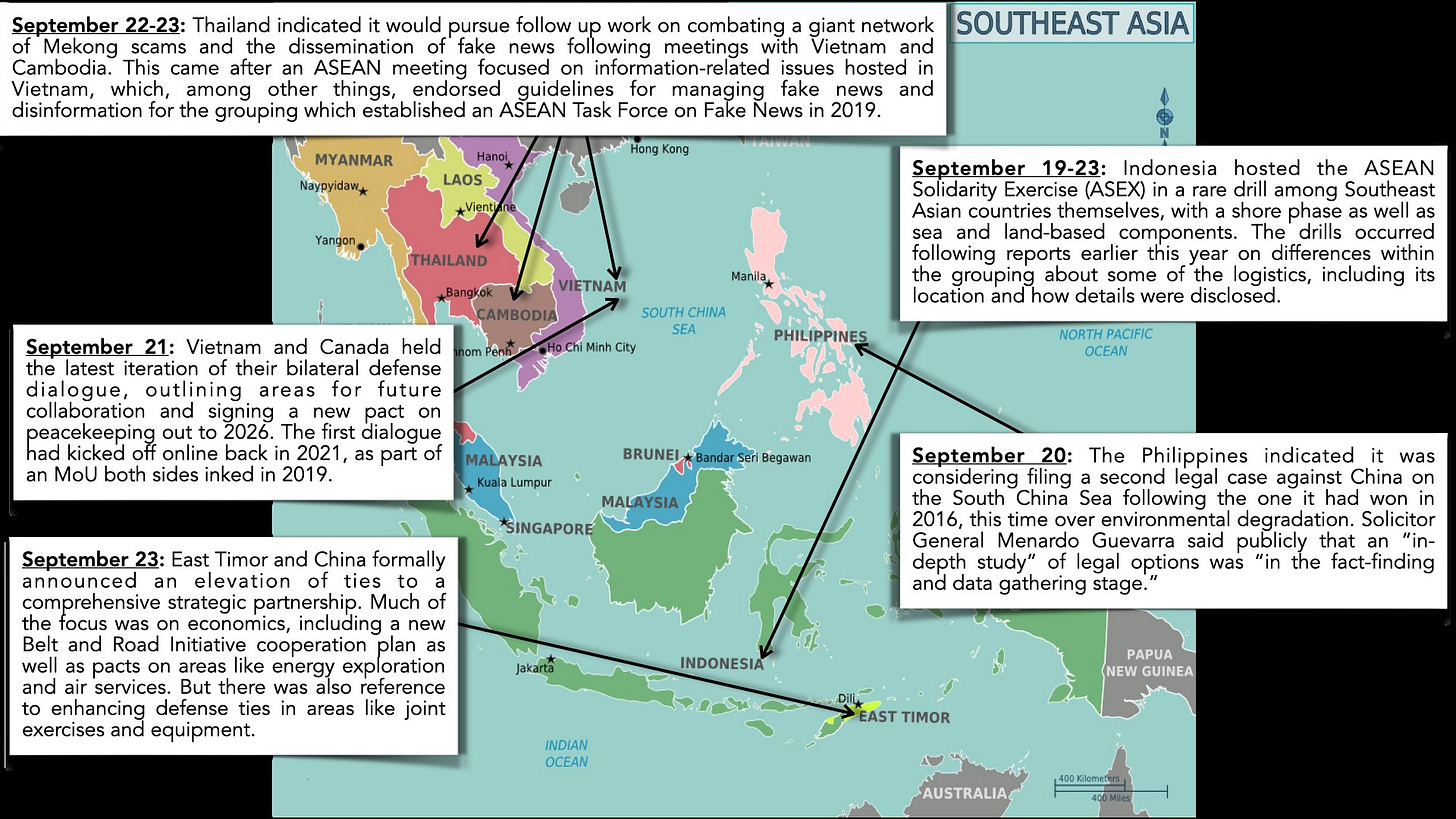

Philippines South China Sea Legal Case Sequel Talk; New China-East Timor Partnership & More

Assessing ASEAN’s New Military Drill: How the 2023 Solidarity Exercise in Natuna Matters

What’s Behind It

ASEAN countries held a rare and much-anticipated exercise between themselves. The exercise, called the ASEAN Solidarity Exercise in Natuna 2023 (ASEX-01N), was hosted by Indonesia — which held the annually-rotating ASEAN chair this year — from September 19 to 23. The publicized focus was around areas such as maritime security and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

The drills were held following reported intra-ASEAN differences over logistics in June including how details were disclosed and its specific location earlier this year. As a result, those familiar with the planning of the drills had noted that adjustments would need to be made. This was especially the case when initial headlines made it seem like the proposed agreed drill location in the North Natuna Sea — which Indonesia had renamed for its portion of its exclusive economic zone back in 2017 — was part of what could be perceived as a more bullish ASEAN stance towards the South China Sea disputes which has found resistance among less forward-leaning countries like Cambodia (only four ASEAN countries formally consider themselves South China Sea claimants, though China’s nine-dash line infringes into parts of Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone).

Why It Matters

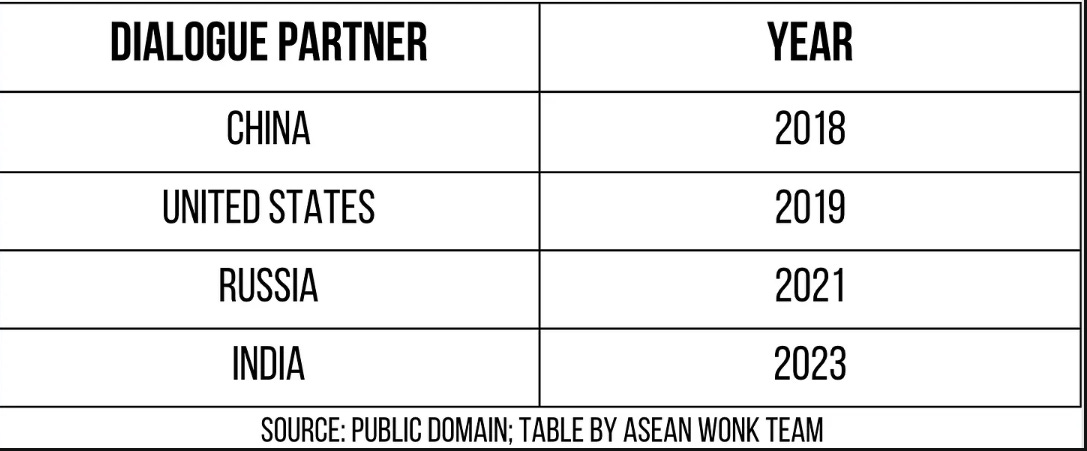

The drills are a milestone by ASEAN standards given the grouping’s relatively recent history in holding these exercises internally and growing worries about its relevance on issues such as the South China Sea. As noted in these pages when the exercises were first mooted earlier this year, hile ASEAN countries hold regular exercises with each other individually and with external partners (see select examples with dialogue partners below), the idea of multilateral exercises among Southeast Asian states is fairly new. Indeed, even the ASEAN Multilateral Naval Exercise (AMNEX) series only saw its second iteration this year hosted by the Philippines, following the first back in 2017 hosted by Thailand.

Select ASEAN Drills with Dialogue Partners

This also marks another maritime-related marker in Indonesia’s chairmanship of ASEAN this year. In addition to the drills, Jakarta has also overseen the publication of the grouping’s first annual maritime outlook, kept the moribund diplomatic track on pursuing a South China Sea code of conduct alive and tried to tie ASEAN’s Outlook on the Indo-Pacific to specific functional issues of concern to Southeast Asian countries such as economic growth.

While the holding of such events are important symbolic moves, they do not in and of themselves change the grim situation for Southeast Asian states in the South China Sea. China is still routinely infringing into what Southeast Asian states consider their waters while also showing few signs of wanting to move forward with a binding code of conduct that would constrain its behavior. Recent actions by Beijing, such as multiple continuous weeks of infringements into Vietnamese waters, firing water cannons on Philippine vessels and publishing a new so-called ten-dash line map suggest few reasons for optimism. Meanwhile, the structural realities that enable China’s behavior, such the massive military gap between China and Southeast Asian states and divisions in approaches — both within claimants and between claimants and non-claimants — remain unchanged.

Where It’s Headed

Looking ahead, all eyes will be on the extent to which ASEAN can regularize the holding of drills among Southeast Asian states themselves moving forward. Though sustaining and annualizing this may seem simple, within an ASEAN context, it is not without its share of obstacles given realities such as the limited military capabilities of some Southeast Asian states and changing priorities as the ASEAN chairmanship rotates on an annual basis. For perspective, it is worth noting for example that similar to the first AMNEX held back in 2017, while ASEX-01N was designated an ASEAN-wide exercise, the level of participation was far from even and only a few countries actually sent ships.

New exercises with ASEAN’s dialogue partners will also be a related development to watch, especially with more drill ideas taking off following pandemic-related interruptions. ASEAN has thus far tried to ensure that it holds exercises with a variety of dialogue partners to manage incoming requests and calibrate engagement on this front, with the latest held with India earlier this year. But there will also be continued pushes for more of these drills that the grouping will need to navigate into the future.

ASEAN Climate Perceptions; Cambodia and Major Power Competition; Southeast Asia’s Ongoing Business Attraction Race

“The proportion of respondents expressing the highest level of urgency on climate has come down from 68.6% in 2021 to 49.4% in 2023,” notes the newest iteration of an annual Southeast Asia climate outlook report published by the ISEAS-Yusok Ishak Institute (see graphic below). Though there is still a robust percentage of respondents who recognize the need to monitor events, the report notes that “this raises the question of whether the association of immediate problems such as energy shortages and insecurity are with climate impacts, geopolitical problems or domestic issues.” (link).

Aggregate ASEAN Views on Climate Change

“Some scholars argue that Cambodia is pursuing a “comprehensive bandwagoning” strategy toward China…while this argument does seem to illustrate the overall picture of Cambodia’s strategy toward China in a nutshell, it does not fully describe the country’s foreign policy direction,” notes the latest iteration of a series of commentaries on Southeast Asian states and U.S.-China competition published by the U.S. Institute of Peace. The piece looks at the implications of intensifying major power competition on Cambodia and the various ways to frame Phnom Penh’s agency and actions (link).

“Malaysia is the leading major destination for companies seeking to enter a new ASEAN market…the Philippines is also a leading target,” notes a new HSBC report that touches on company expansion plans within Southeast Asia. Apart from who leads in an overall sense, the report also divides up countries by where prioritization lies by firm source, with notable differences for companies from Australia, China, Europe, India, the Middle East and the United States. Overall, the report finds that Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand still remain preferred growth routes for existing companies (link).