What's in the New China-ASEAN South China Sea Pact?

Plus Thailand's Myanmar diplomacy; regional stakes in the critical minerals landscape; revived Malaysia-Singapore high-speed rail chatter and more.

Welcome to this week’s edition of the ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! For this iteration, we are looking at:

Evaluating the ASEAN-China South China Sea agreement on guidelines to accelerate code of conduct talks;

Mapping of key regional developments including Thailand’s Myanmar post-coup diplomacy and the Philippine commemoration of the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling;

Charting evolving trends related to the regional stakes in the critical mineral landscape and developments in the forestry sector in Indonesia and Malaysia;

Tracking and data-driven analysis of industry developments such as China-Cambodia cooperation on cross-border payments and Tesla’s investments in Malaysia;

And much more! (ICYMI: Check out the first iteration of our new ASEAN Wonk SpeedRead series where we review longtime U.S. diplomat Scot Marciel’s new book on U.S.-Southeast Asia relations).

WonkCount: 1,667 words (~ 8 minutes reading time)

ASEAN Ministerial Meet; Thailand’s Post-Coup Myanmar Diplomacy; Philippines South China Sea Case Anniversary & More

What’s in the New China-ASEAN South China Sea Pact?

The new ASEAN-China agreement on guidelines to accelerate progress on the ever elusive South China Sea code of conduct is a tangible demonstration of Indonesia’s earlier commitment to inject new momentum into moribund talks, but it also continues to expose the vast gap between Beijing’s words at diplomatic meetings and its actions on the water as well as raise concerns about ASEAN’s relevance in managing the issue amid its manifold challenges.

What’s Behind It

ASEAN and China agreed on guidelines to accelerate negotiations for the code of conduct (COC) in the South China Sea. The agreement on the guidelines was reached during the ASEAN post-ministerial conference with China on July 13, which was part of a series of meetings led by Indonesia as this year’s ASEAN chair. Indonesia had said since the early phase of its chairmanship that its objectives would include trying to inject more momentum into COC talks through incremental measures, which date back to the 1990s and have continued since the adoption of a non-binding Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) in 20021.

The agreement comes amid ASEAN’s increasingly worrying position on the South China Sea in recent years as noted previously in these pages (see a few select recent regional developments in the graphic below). Chinese forces are continuing to routinely harass Southeast Asian states through interceptions of exploration work and dangerous maneuvers while Beijing drags its feet diplomatically. Meanwhile, states are pursuing their own responses at sea on their own and with others, as evidenced by the Philippines’ acceleration of its involvement in minilateral security initiatives and more outspoken approach to Chinese incursions or Vietnam’s expansion of its outposts2.

Select Recent Regional South China Sea Developments

Why It Matters

Despite decades with little progress, both ASEAN and China have their own interests in keeping the diplomatic track alive. China needs to demonstrate continued participation within the ASEAN process in this area as it advances other components of ties with the bloc, particularly in the economic domain. More active ASEAN members like Indonesia recognize that though the grouping’s ability to shape outcomes may be limited, some advances need to be worked out to preserve its credibility and minimize damage to its unity and centrality. Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi notably framed the ASEAN-China South China Sea agreement on guidelines as part of a bigger picture where if China is to be a reliable partner for both sides to achieve win-win cooperation, they “must continue to build positive momentum” that “respects international law including UNCLOS 1982” and "promotes habits of dialogue and collaboration”3. The connection to the illegality of China’s nine-dashed line, and its far from collaborative actions in the South China Sea, was clear.

Both sides still have the same tough issues to work through if they are to eventually get to a meaningful code of conduct. Previous rounds of talks have centered on disagreements such as whether or not a COC ought to be binding — a longstanding matter that played into the eventual adoption of the DOC in the first place — and what its geographical scope should be. Though the full new agreement has yet to be publicized, indications are that substantial sticking points remain4. In recognition of the reality that it is equally important to focus on what a COC ought to accomplish rather than just inking a document for its own sake, the joint statement released following the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting mentions "the early conclusion of an effective and substantive COC that is in accordance with international law, including the 1982 UNCLOS.”5 The reference to international law came just after the commemoration of the anniversary of the international arbitral tribunal ruling on the Philippines’ South China Sea case issued back in 2016, which Manila had partly undertaken due to its frustration about the lack of inroads within ASEAN.

Where It’s Headed

Looking ahead, the South China Sea issue is likely to loom large for the rest of Indonesia’s chairmanship and out to the transition to Laos as 2024 chair. Indonesia announced earlier this year that ASEAN would hold its first drills related to the South China Sea in September, and given the headlines it generated, with the location since shifted to the South Natuna Sea, it will be a development to watch. Despite Laos largely defying anxieties about its chairing of ASEAN back in 2016, its chairmanship in 2024 will still likely not be short on worries, including on any South China Sea actions or statement wordings — even if they fall short of ASEAN’s unprecedented failure to adopt a joint communique during Cambodia’s watch back in 2012. Further out, if progress is to be made in talks in the coming years, part of the discussion will be around which chairmanship year we are likely to see inroads announced, especially since only four of the ten ASEAN states (eventually eleven when East Timor is fully admitted) are officially South China Sea claimant states, with others being a mix of interested and less interested parties.

Questions around ASEAN’s broader relevance on the South China Sea issue show few signs of easing anytime soon. As noted previously in these pages, while Indonesia’s injection of a dose of activism for ASEAN on the South China Sea issue is a welcome move, the broader structural realities still point to a significant and growing risk of the grouping’s marginalization, with individual Southeast Asian states taking matters into their own hands, major powers exerting a greater influence, minilateral mechanisms moving at a faster clip and previously mulled measures like easing consensus-based decision-making through “ASEAN Minus X” mechanisms showing few signs of making major inroads quickly. Optimists may see this ASEAN-China effort to accelerate talks as an opportunity for ASEAN to at least remain somewhat relevant on the issue.

China-Philippines Buoy Wars; Regional Stakes in the Critical Minerals Landscape; Improving Forestry Metrics in Indonesia and Malaysia

Buoys Placed in the Spratly Islands (May 2022-May 2023)

“But while the current round of buoy competition appears to be over, tensions are slated to crop up again later this year when the Philippines plans to deploy another round of six buoys in the South China Sea,” notes an update from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative on the China-Philippines buoy deployment in the Spratly Islands. The update argues that likely locations of additional buoys include Commodore Reef and Second Thomas Shoal – the only two Philippine-occupied reefs without a buoy – in addition to Scarborough Shoal, Iroquois Reef, Sabina Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal (link).

“There has been limited progress in terms of diversification over the past three years; concentration of supply has even intensified in some cases,” notes the first-ever iteration of the Critical Minerals Market Overview published by the International Energy Agency. Southeast Asian states are an important part of that picture (see graphic below), whether it be Indonesia and the Philippines which make up a majority of the world’s nickel or the role of Myanmar and Vietnam in the composition of China’s unrefined imports in tin and lithium respectively, the diversification of which the IEA says “hint at greater competition for mining assets across the world” (link).

Share of Top Three Producing Countries For Selected Resources (2022)

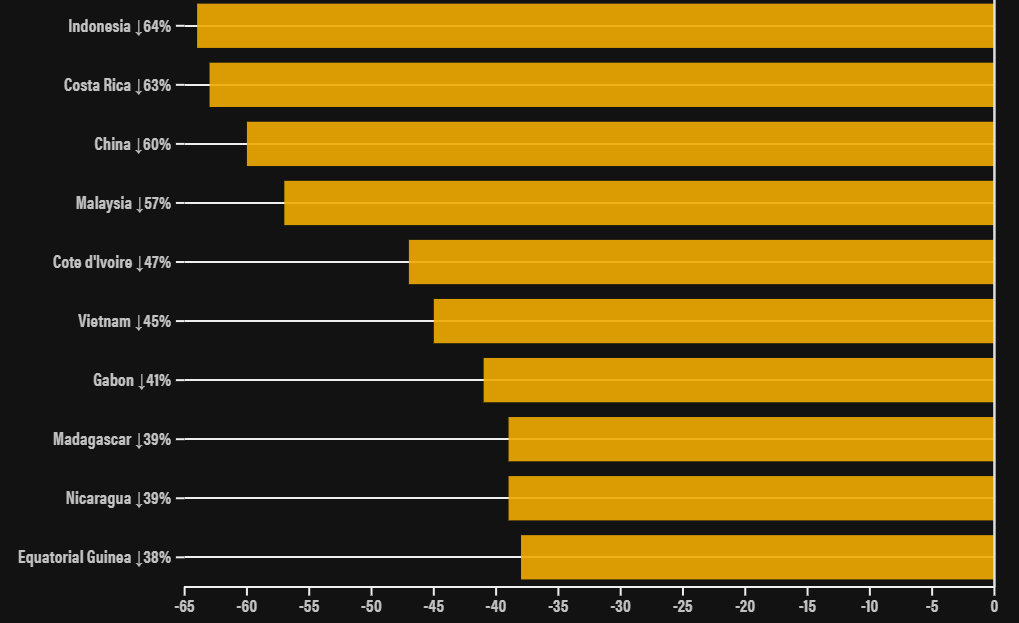

“Indonesia has reduced its primary forest loss more than any other country in recent years,” observes a report by Global Forest Watch (see ranking below). Though challenges still remain on this front, the report credits a mixture of government policies and corrective actions — including on fire monitoring; licensing; and rehabilitation — along with cloud-seeding efforts involving the private sector, corporate commitments and on-the-ground community efforts (link).