Southeast Asia in 2026: Geopolitics and Geoeconomics Outlook

Looking ahead to five critical 2026 items to watch in Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific, with trends, datapoints, trendlines and much, much more.

Dear Readers - Today, we at ASEAN Wonk are pleased to launch the 2026 iteration of “FuturePoints,” our annual assessment of the top five geopolitical and geoeconomic datapoints and trendlines to watch impacting Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific region. This iteration looks at the top five developments for 2026. If you have not already, do consider subscribing below to receive full posts and support our work! And if you have already done so, do consider forwarding this to others who may be interested. Thank you for your support!

Some readers have asked how they and their institutions can contribute to ASEAN Wonk’s development during this holiday season and discuss other forms of strategic collaboration. Apart from reaching out to us on subscription options, feel free to email us at aseanwonk@gmail.com if you have further questions or inquiries in this regard and we would be glad to discuss!

WonkCount: 2,926 words (~13 minutes).

1. NEXT UPGRADE PHASE BEYOND US CHINA “G2 FLUX”

Line of Sight

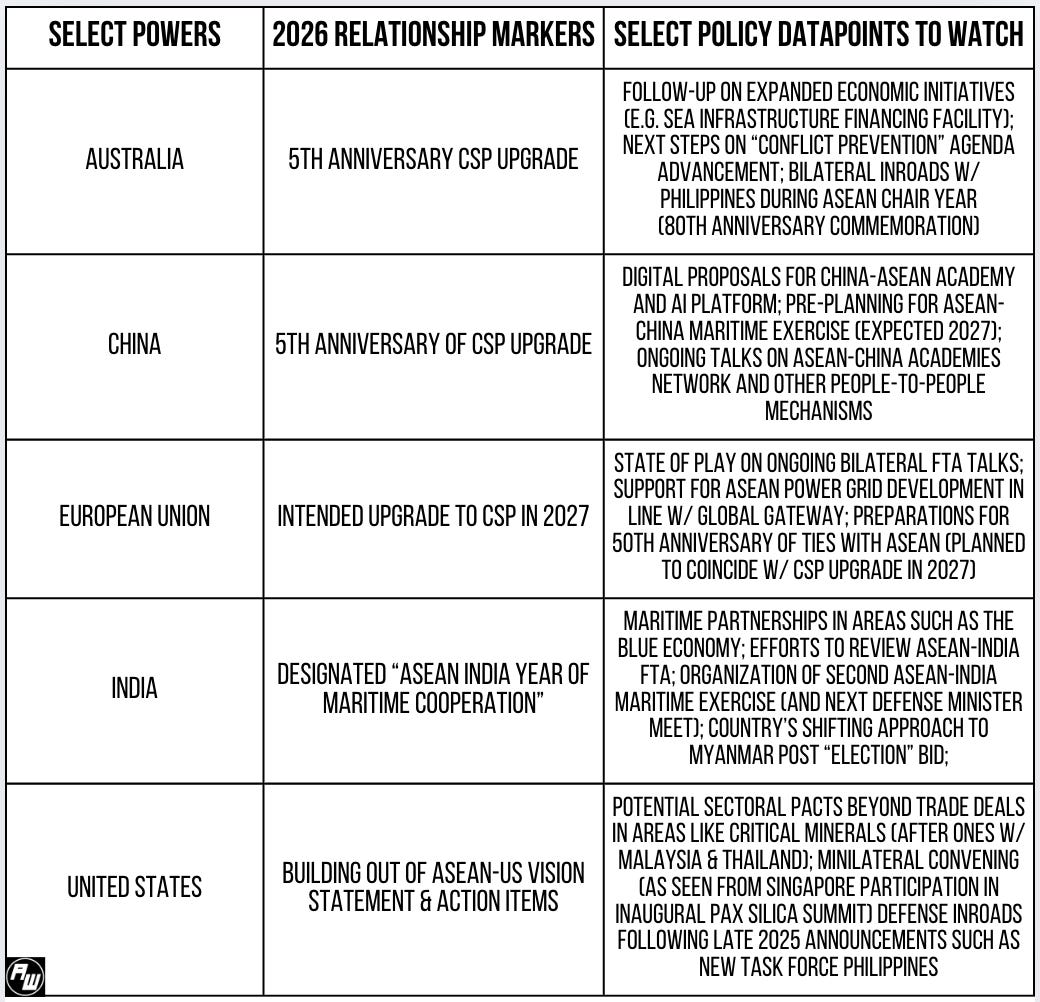

Key powers in Southeast Asia will be adjusting to the next upgrade phase in 2026 beyond the focus on US-China dealmaking and “G2 flux.” Upgrading is clearest in the ASEAN context, where China along with Australia will be the first in line in 2026 for the the five-year ASEAN stocktaking exercise on comprehensive strategic partnerships (CSPs), providing opportunities to raise the bar on bilateral and regional ties (Beijing and Canberra were the first two of ASEAN’s dialogue partners to establish CSPs with the grouping agreed back in 2021). These varying policy cycles are one among many reasons why defining influence in what one official called “G2 flux” around datapoints like U.S. President Donald Trump’s potential April China visit can be an overly narrow prism. Diversification tendencies have been reinforced in much of the region engaging with the third consecutive single-term U.S. administration and a China that sees opportunity to push even further ahead of Washington as what official described as the “most leading” partner and “self-evident” choice in some domains1.

Select Policy Datapoints to Watch, Along with 2026 Relationship Markers and Key Powers

Over the Horizon

Looking ahead, the evolution on engagement dynamics and agenda items will be a theme to watch apart from earlier “void-filling” hype. China has floated an initial list of over two dozen commemorative activities for the year, and it has not gone unnoticed that the optics have been heavily focused around the bucket of issues traditionally classified as science, technology and innovation (given sectoral competition underway in key domains) along with people-to-people ties (which provides Beijing an opportunity for oneupmanship amid concerns around shifting U.S. immigration policy)2. Australian officials for their part have signaled in their regional agenda for 2026 that while the country has its own share of domestic challenges, Canberra is doing its part on areas like education as well as development assistance following global aid cuts. Apart from the country’s economic focus on shoring up what the government has admitted ought to be stronger investment and business links to the region, a notable datapoint on the security side is the evolution of the country’s approach to regional conflict prevention which its foreign minister has highlighted3.

Under the Radar

Engagement by other powers either preparing for the next upgrade phase or consolidating recent elevations will also be a key datapoint. One notable case in point is the European Union, which has rolled out sector-specific initiatives including in the energy, climate and infrastructure domains as it looks to upgrade ties with ASEAN to the CSP level by 2027 which will mark the 50th anniversary of ties. Another is India which along with Washington will see its CSP with ASEAN approach its 5th year anniversary in 2027. New Delhi has floated new defense-related initiatives such as another maritime exercise and ministerial meeting, but it has found it more challenging to translate bilateral partnership inroads with individual Southeast Asian states into new regionwide economic initiatives4.

2. TRIPLE MAINLAND TRANSITIONS

Line of Sight

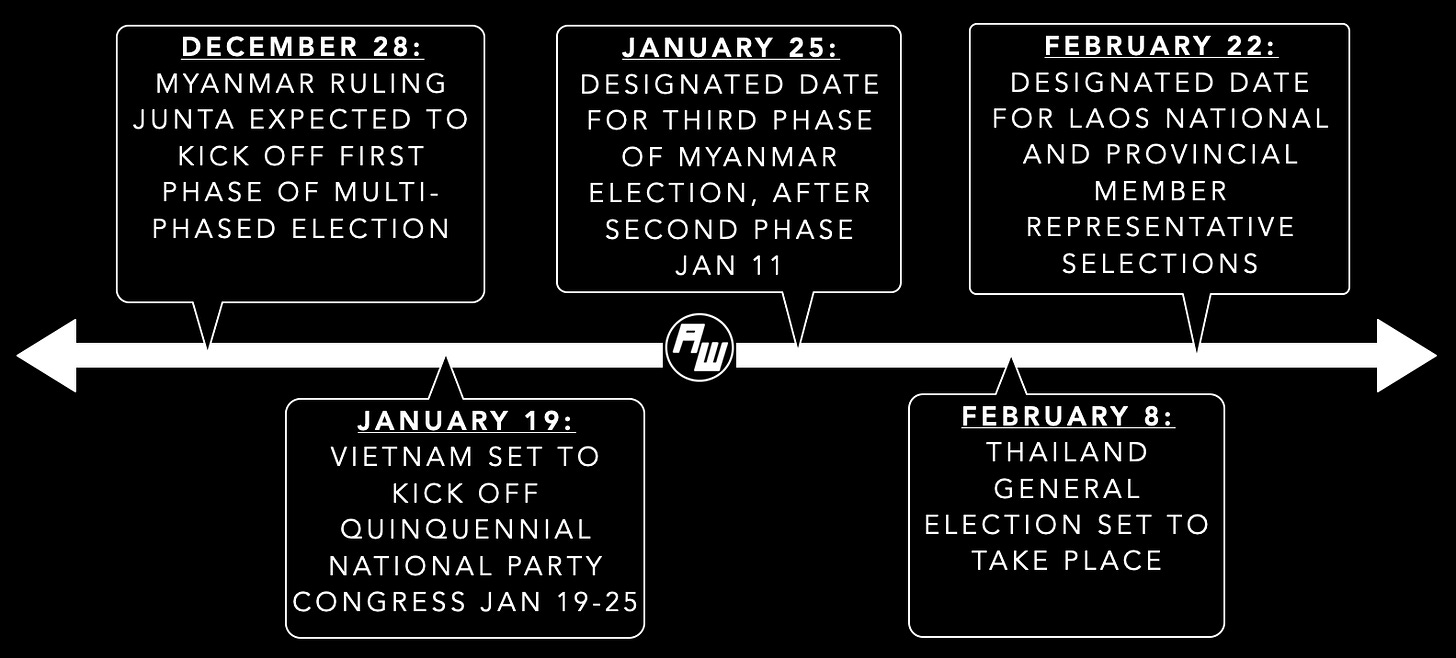

2026 will be shaped by triple transitions in mainland Southeast Asia occurring in Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam during the first quarter of the year, with implications for subregional and wider geopolitical dynamics across realms since the three countries account for about 90 percent of the subregion’s population. The Myanmar junta’s so-called multi-phased election bid kicks off its first phase on December 28, with subsequent plans for two further phases next year in January 2026 as well5. Thailand’s general election is set to take place on February 8, while Vietnam’s communist party will be holding its quinquennial national party congress starting mid-January which will see key appointments, plans and goals finalized.

Select Key Transitions in Mainland Southeast Asia

Over the Horizon

Looking ahead, conflict futures will be a major storyline to watch. The fact that Thailand’s election is taking place amid the reigniting of the country’s border row with Cambodia reinforces the role of evolving domestic politics in conflict dynamics, which one government advisor recently characterized bluntly as being rooted in long overdue leadership changes in one country and overly frequent leadership changes in the other country6. In Myanmar, much of the concern is around violence that will accompany polls and the shape of a “managed transition” said to be in place by the end of March 2026. Southeast Asian officials — particularly from so-called frontline states like Thailand — are not unaware of the risks of regional failure in managing a crisis that spirals out of control and sparks greater calls for more global intervention.

Under the Radar

While often overlooked, evolving political timelines for Cambodia and Laos also remain important to watch. On Cambodia, as much as recent moves like kickstarting of U.S. defense drills help Phnom Penh downplay China dependence, Cambodia has recently displayed a tendency of tilting more in the direction of Beijing when it transitions to elections (local elections are currently set for 2027, followed by national elections in 2028). Laos will also be going through its own domestic political transition in early 2026, with designated dates for national and provincial member representative selections also publicized earlier this month7. Beyond periodic headlines on China legal hydropower tussles and cryptocurrency mining readjustments, serious governance challenges have also been at play in quieter domestic steps including ministerial mergers and restructuring.

3. GEOECONOMIC REBALANCE TEST

Line of Sight

2026 will be a litmus test of extent to which rhetoric around geoeconomic rebalancing is concretizing into reality. Though 2025 produced a wide range of first-of-its-kind developments – including the first-ever ASEAN-China-Gulf-Cooperation Council Summit and Singapore’s new Future of Investment and Trade Partnership (FITP) – policymakers also privately concede these pale in comparison to wider challenges around geoeconomic rebalancing that transcend oversimplifications such as diversifying to export destinations beyond the United States or managing so-called “overcapacity” from a “second China shock.” Just as one example, while Vietnam is recognized as being among the most active engagers in Southeast Asia, officials have noted that export diversification would need to account for a reality that around 50 percent of the country’s exports go to either China or the United States by one count amid shifting interpretations by U.S. administrations about what constitutes “transshipment”8.