The Future of Singapore Foreign Policy: A Coming Grand Strategy Shift?

A closer look at what Singapore's grand strategy says about the trajectory of its future approach to foreign and defense policy.

A newly-released book sets out Singapore’s grand strategy at a time of heightening domestic, regional and global challenges for one of the region’s most diplomatically active and militarily capable states.

WonkCount: 1,955 words (~ 9 minutes)

Context

“A small country must seek a maximum number of friends, while maintaining the freedom to be itself as a sovereign and independent nation. Both parts of the equation – a maximum number of friends and freedom to be ourselves - are equally important and inter-related,” Singapore’s late founding father Lee Kuan Yew said at a lecture back in 2009 in reflecting on the enduring fundamentals of Singapore’s foreign policy since its independence in 19651.

Nearly a decade and a half after that speech, that equation would seem more challenging to achieve than ever. Abroad, Singapore’s top officials have warned privately and publicly that the backlash against trade, strains in regional and international institutions and the risks of bifurcation in U.S.-China competition have complicated the environment within which small states operate2. At home, Singapore is also preparing for a delayed transition to a new generation of leadership as it confronts issues ranging from the threat of foreign interference to refreshing its social compact3. Occassional inflection points, such as Singapore’s so-called “small state debate,” have also highlighted aspects of a public conversation over how the country should move forward4.

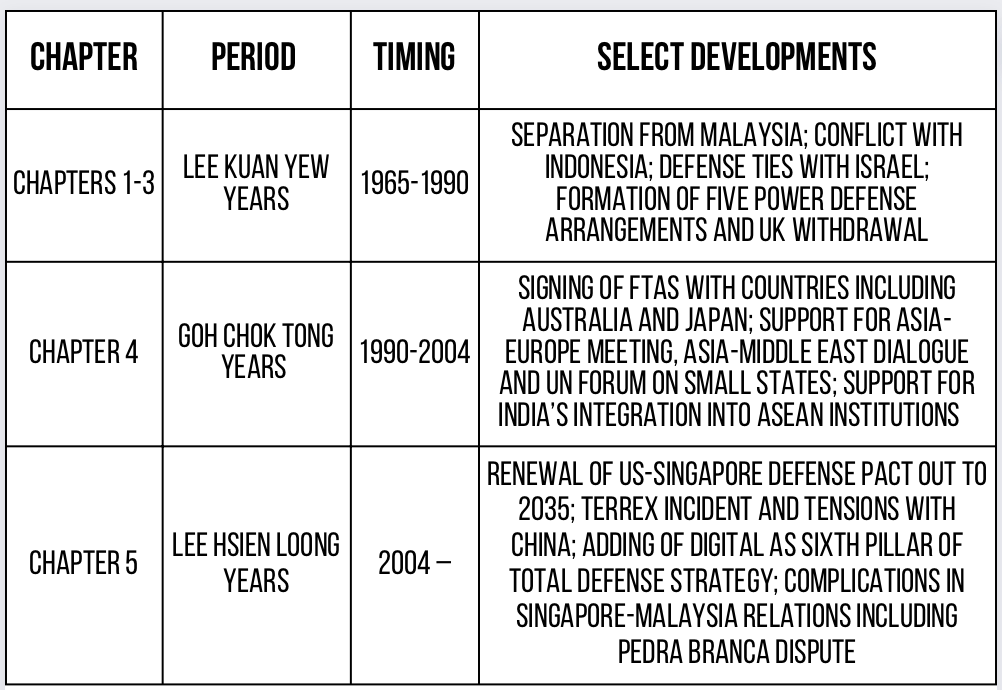

A new book titled Singapore’s Grand Strategy by scholar Ang Cheng Guan examines the origins, evolution and future prospects of Singapore’s foreign policy approach amid this shifting context. The book argues that Singapore’s multifaceted grand strategy since independence has centered on its survival and independence as a nation-state, which plays out in its management of ties with its neighbors, its approach to major powers as well as its policies around particular realms such as multilateralism, defense and international law5. The book traces this over three periods in line with its three prime ministers thus far: the Lee Kuan Yew years (1965-1990); the Goh Chok Tong years (1990-2004); and the Lee Hsien Loong years (since 2004) (see table below for a summary of key chapters and topics covered).

Periods and Select Developments in the Evolution of Singapore’s Grand Strategy

Analysis

The book confronts a major question: is it possible to discern a grand strategy in Singapore’s foreign policy, and, even if it is, to what extent is it useful in assessing continuity and change in practice? This is a question that transcends Singapore, and there are different views on it even within the country. For example, Bilahari Kausikan, one of Singapore’s top ex-diplomats (whose latest book ASEAN Wonk reviewed here), has argued that the idea of a grand strategy can downplay the prevalence of incoherence and improvisation in foreign policy practice, where apart from setting certain goals which may themselves change, “[a]ll one can do is keep a distant star in sight even as one tacks hither and thither to avoid treacherous reefs and shoals or to scoop up opportunities that might drift within reach.”6

Singapore’s Grand Strategy makes the case for what the outlines of a “distant star” might look like for Singapore, looking at principles which it contends have been remarkably consistent since independence. Unlike some accounts that focus singularly on the role of Lee Kuan Yew, the book acknowledges the reality that Singapore’s founding father also had capable figures around him which helped shape the country’s grand strategy as well, such as Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam. It also usefully situates the argument within the global scholarship on grand strategy, which has been written about by scholars such as Hal Brands, John Lewis Gaddis, William Martel and Nina Silove7. This makes it a useful addition to the few books written on Singapore’s external relations to date, including those focused on foreign policy (like Bilveer Singh’s The Vulnerability of Small States Revisited or Michael Leifer’s Coping with Vulnerability) and defense policy (such as Tim Huxley’s Defending the Lion City)8.

Singapore’s Grand Strategy also offers an important reminder that amid the focus on major power competition today, variables closer to home, like domestic vulnerabilities and bilateral regional relationships, often play a more important role in shaping the country’s approach to the world. Take for instance the close U.S.-Singapore ties we see today, the origins of which began taking shape in the mid-1960s. As the book notes, Singapore’s leaders, some of whom harbored suspicions about Washington as a power and did not foreclose the possibility of closer future ties with China, came to see the United States as a useful contributor to a “non-racial balance of power” in Southeast Asia amid the country’s tensions with larger neighbors Indonesia and Malaysia; external fears that it would become a Chinese satellite state; the regional withdrawal of Britain as the traditional regional security provider; and the need for a stable regional environment for growth9.

Similarly, Singapore’s development of an “external economy” in the 1990s and 2000s, which saw it sign a series of free trade pacts and boost foreign investment, was partly rooted in domestic and regional realities. This included the absence of an inner hinterland, the lack of progress in economic ties with neighboring Southeast Asian states with Malaysia as well as the limitations of ASEAN which Singapore’s policymakers had realized early on10. For those interested in the future trajectory of Singapore’s foreign policy, the book offers a sense of where some of the key principles of its grand strategy are headed based on some key reference points (see table below).