Indo-Pacific Security Networking in the Spotlight Ahead of Upcoming US-Philippines Expanded Balikatan Drills

Plus Indonesia-Singapore security pacts; rethinking Indo-Pacific strategic competition; "chronic factionalism" in Myanmar's civil war; and more.

Welcome to the ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief newsletter! On behalf of the ASEAN Wonk team, I’m Dr. Prashanth Parameswaran. We hope you enjoy the first iteration of this new weekly newsletter, which is designed to provide bulleted insights with a 360-degree, global view on Southeast Asia security and foreign policy.

Each week, we’ll bring you a mix of our own policy-relevant, data-driven insights and curated analysis from regional and global practitioners, with the goal of capturing the region’s growing international stature and the comprehensive nature of security thinking - between ballots, bullets, bonds and much else. Free subscribers get a window into one or two of the weekly newsletter’s five sections, while paid subscribers will get the full version regularly and additional forthcoming exclusive content, including interviews and deeper data dives. If you’re a free subscriber and like what you’re reading, consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Feel free to send tips and thoughts to prashanth.aseanwonk@gmail.com. You can also follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn to stay in touch professionally. If you’d like to share this with others, feel free to use the link below.

Let’s dig in to this week!

This week’s WonkCount: 2209 words (around 11 minutes read time)

Philippines Security Networking in Perspective Ahead of Upcoming Expanded Balikatan Drills

While the headlines may be focused more on the exact shape of the upcoming U.S.-Philippine Balikatan exercises, the broader strategic question is what the prospects hold for Manila as a node for intensifying Indo-Pacific comprehensive security networking under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr after a period of challenge under his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte.

What’s Behind It:

The focus on Balikatan is part of broader renewed hope for greater security networking within the U.S.-Philippine alliance under Marcos. As I noted in my book Elusive Balances, despite the decades-old notion of networking U.S. alliances from a more traditional hub and spokes notion – portrayed in various ways including “from wheels to webs” – finding sustainable hubs to anchor such conceptions is not without its challenges and the Philippines is no exception, with previous contestation on issues ranging from clarity on security assurances to the closure of U.S. bases to Duterte’s threats to cancel Balikatan and “separate” from the United States. Since coming to office last year, the Marcos administration has thus far signaled a return of promise on the security networking front in words and actions and ties more generally, with potential traction seen on previously floated initiatives including joint drills in the South China Sea and Visiting Forces Agreement-like pact with Japan.

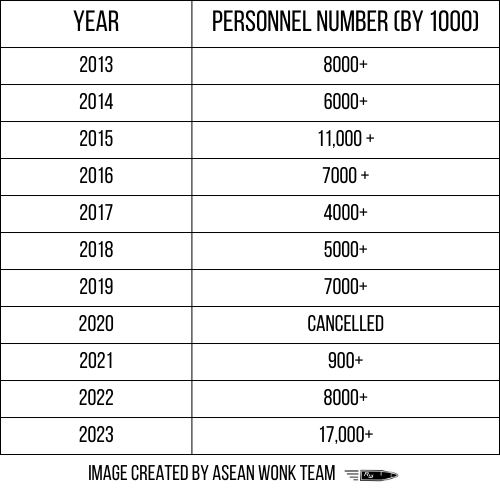

The prelude to the drills has highlighted some of the manifestations of expansion, some of which had been mulled in the pre-Duterte period. Philippine media has publicly cited over 17,000 Filipino and U.S. troops participating in the exercises in April in the largest iteration to date, with some participation from Australia and Japan as well as had been the case previously. Philippine officials have also played up components such as cyber defense exercises and live fire exercises at sea occurring outside traditional areas which will enable to utilization of more service components. If you map out the yearly numbers for Balikatan, 17,000 would put it at a nearly 50 percent increase from the last record level back in 2015 during the late Obama years and before Duterte came to power, where they declined in numbers, were briefly canceled and then were scaled down amid COVID-19 (see a quick summary of the numbers below).

Why It Matters:

If this continues to progress as intended, it could reinforce Balikatan’s role in the growing minilateralization and regionalization of the U.S.-Philippine alliance and a force multiplier for security networking. Though obviously a different case, the other major example by way of a U.S. treaty ally, the Cobra Gold exercises held in Thailand and now one of the world’s largest multinational security drills, grew from more limited U.S.-Thailand alliance interactions. Networking also has implications for future crises - whether it be in a Taiwan contingency, which Philippine officials are being increasingly vocal about, or even natural disasters - far from just a talking point as Manila is one of the world’s most disaster-prone countries.

Beyond these macro geopolitical implications, this could also have implications for the meeting of the Philippines’ tangible needs, which could emerge organically apart from scheduled engagements. To take just one example which has not gotten nearly as much attention as it should, Japan’s quick recent assistance to the Philippines following one of the country’s largest oil spills in its history attests to Tokyo’s own role as a comprehensive security partner, which had also endured under the Duterte administration.

Where It’s Headed:

Beyond Balikatan, tangible examples of networking – including beyond traditional security – and a firmer development of Marcos’ foreign policy will be needed to draw clearer conclusions. The initiatives proposed, including a VFA-like agreement with Japan and joint patrols in the South China Sea, are not new, and progress will require sustained political will and follow through amid Beijing’s attempts to undermine them, including through potential coercion.

Shifts in the Philippines’ outlook should also not be ruled out as internal and external dynamics evolve. Every leader ought to be judged on his own merits, but it is worth recalling that previous Philippine administrations have calibrated their own approaches within their single six-year tenures as well. Benigno Aquino III initially engaged China but shifted to a firmer pro-U.S. tilt amid Beijing’s growing maritime assertiveness, while Duterte, despite an announced “separation” from the United States, oversaw greater collaboration with Washington towards the end of his tenure in part because he saw the increasing value in doing so, including U.S. assistance following the 2017 Marawi siege by Islamic State-backed militants.

Cooperation in the Bay of Bengal; Rethinking Security Competition in the Indo-Pacific; China and the South China Sea Internet Cable Landscape

“While the Bay of Bengal is located at the fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific, between the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, it continues to act more as a divider than a link between land and maritime neighbours such as India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Thailand or Indonesia.,” notes a report for the Center for Social and Economic Progress with a comprehensive look at key areas. The paper on maritime security cooperation, for instance, makes the case for collaboration between South and Southeast Asia in areas of irregular human migration and illicit drug trade (see a UNODC graphic above on regional crystalline methamphetamine trafficking flows featured in the paper). Recommendations include investing in smaller-scale, subregional initiatives like BIMSTEC, promoting better coordination among national agencies in areas like drug trafficking, building out regional mechanisms for Rohingya refugees via the Bali Process and utilizing India’s Information Fusion Center-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR).

“There is a growing acceptance among countries in the Indo-Pacific region that strategic competition between the United States and China is changing perceptions about security and the adequacy of the existing security architecture,” reads a new volume on security and strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific region by the Pacific Forum, following a conference held on the subject in Singapore which I attended late last year as a contributor. It includes a chapter from me looking at the role of economic institutions, where I argue that the proliferation of these institutions – ranging from sectoral agreements on digital and the green economy to the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework – has blurred the line between economics and security, decentered the regional landscape away from multilateralism, and granularized the space for competition and collaboration among major powers beyond just the United States and China, including actors like Japan which have led conversations in areas like economic security.

“Several sources said that to avoid deadlock over permits, subsea cable consortiums were now seeking to forge new routes that circumvent China’s claimed waters,” per a piece by The Financial Times on how Beijing is reshaping the internet cable landscape in the South China Sea. The article, which is mostly anonymously sourced due to cited sensitivities, argues that Beijing has begun to impede projects to lay and maintain subsea internet cables through the South China Sea, with long approval delays and stricter Chinese requirements pushing companies to design routes that avoid the South China Sea. This is despite the fact that alternative options are both more expensive and could take longer, amounting to what one industry source called “digital infrastructure decoupling” and “double punishment.”

What’s Next for the New Indonesia-Singapore Security Pacts?