China-Thailand Submarine Deal Engine Snag in the Headlines

Plus a new first for EU space partnership in Southeast Asia; maritime disputes beyond the South China Sea and more.

Welcome back to ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! This week we’re looking at the status of the China-Thailand submarine deal; a new first for EU space partnership in Southeast Asia; maritime disputes beyond the South China Sea; and much more.

If you like what you’re reading, consider a paid subscription to get acess to the full weekly BulletBrief as well as other exclusive analytical products.

Feel free to send feedback and thoughts to prashanth.aseanwonk@gmail.com. You can also follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn to stay in touch professionally.

Let’s dig in!

This week’s WonkCount: 2,889 words (~13 minutes reading time)

China-Thailand Submarine Deal Engine Snag in the Headlines

The latest conditions reportedly publicized by Thailand for a modified ship engine to power a submarine China is building for it belies the broader, ongoing saga of Bangkok’s billion-dollar purchase of three boats that had initially raised concerns about Beijing’s regional security inroads and the implications for the U.S.-Thai alliance.

What’s Behind It:

Thailand’s navy commander reportedly laid out the conditions under which the country would be prepared to accept a modified ship engine from China for submarines it is building for Bangkok, given that China is unable to buy a German engine due to the European Union’s arms embargo on Beijing. China’s did not issue its own reading of what those conditions were beyond the generalities of the visit. But Admiral Choengchai Chomchoengpaet said that the three conditions were that the engine would need to be safe, be guaranteed and accompanied by compensation for delays due to the engine change.

This is just the latest in a series of back-and-forth discussions on the engine issue, which is only one of a series of challenges that have bedeviled the deal since it was first publicized back in 2017. Since Thailand reached the deal with China, the Thai government has seen domestic scrutiny over not just the mechanics of the deal, but the logic of submarines for Thailand and its costs amid the economic fallout from COVID-19 and growing pressures on the defense budget (see the graph below on a snapshot of the aggregate budget constraints picture). Over the past few months, both sides have been trying to work out a way to keep discussions going through various means, including RTN officers quietly journeying to observe performance tests on the engine directly earlier this year.

Why It Matters:

This is the clearest indication we have to date of Thailand’s conditions for the engine issue and where it stands. Previously, the RTN had publicly disclosed whether it had decided on whether or not it would agree to replace the engine China is pushing as a substitute for the German one to keep the deal alive. Meanwhile, episodic domestic political opposition has not stopped within Thailand for what was initially one of the most expensive single acquisitions in the country’s history within its decades-long quest for a submarine capability.

More broadly and rightly or wrongly, this continues to be seen as a litmus test of China’s ability to deliver on key defense deals, even though this misses the broader strategic inroads Beijing may look to make in the face of expected obstacles. From the deal’s outset, despite the initial hype of this being seen as a perceived gain for China in trying to capitalize on U.S.-Thai alliance troubles following the 2014 coup, the complexity of submarine deals in general and the domestic scrutiny on this one in particular suggested that there was a risk that it could eventually go the way of an effective death by a thousand cuts, ravaged by prolonged delays, cost issues, and politics. Meanwhile, zooming out, though China continues to make inroads with Thailand across issue areas, the U.S.-Thai alliance is also in relatively better shape than it was in the post-2014 coup aftermath, with publicized manifestations including a new “2 + 2” strategic and defense dialogue, a greater focus on areas like energy security and supply chain resilience and the incremental expansion of the Cobra Gold exercises in a post-pandemic context - one of the world’s largest multinational exercises of its kind.

Where It’s Headed:

While the conditions may have been laid out, the focus shifts now to whether both sides can agree on follow up steps to see them being met, with implications for the broader deal. Choengchai said that China would have until June to guarantee the modified ship engine’s safety which would determine if the contract would go through or would be canceled, and that, if Beijing agreed to the conditions, the submarine could be delivered in 40 months. Yet he also noted specifics would need to be worked out, including the state-owned China Shipbuilding and Offshore International Co. Ltd. offering a guarantee which would be longer than usual and providing support including engine maintenance. He also directly noted that decisions on the second and third boats may need to be postponed, which means the broader saga could drag on even further.

While the progress on the engine issue is noteworthy, the key question is how it will affect the mix of variables around the delivery of the boats. Few details have been publicly released about exactly how the engine will be modified, beyond the fact that the CH620 engine would be tweaked to fit into the Thai submarines being built. Beyond the engine issue, there are other structural issues that continue to loom, including domestic political dynamics following Thailand’s upcoming election and the state of its economy in the quest within Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific for post-pandemic growth.

Southeast Asia Disputes Beyond the South China Sea; US-Japan-Philippines Trilateral Cooperation; ASEAN’s Rising Climate Challenge Stakes

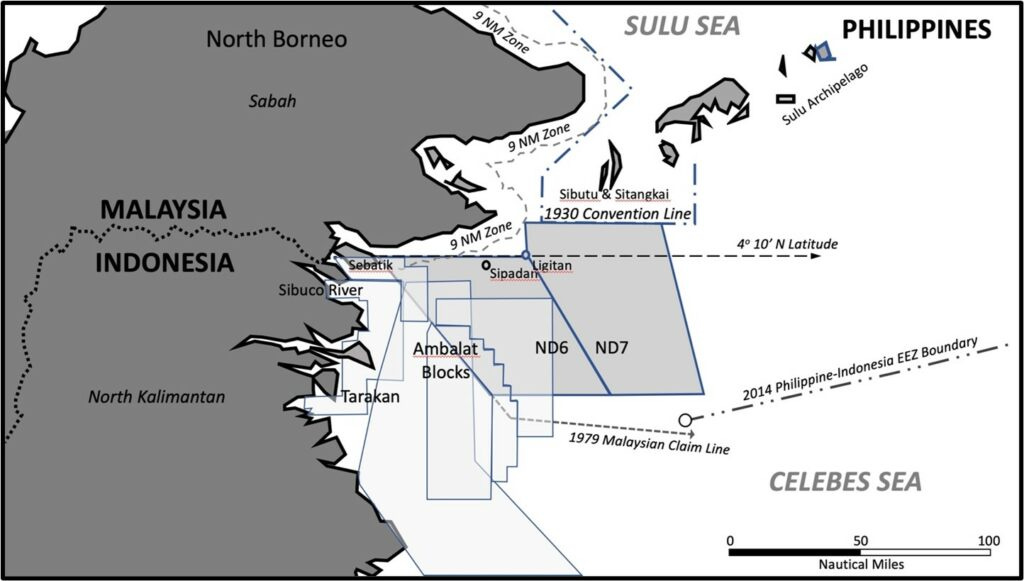

“It would certainly be in the interests of the region for Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines to find the common ground upon which they may settle these complicated territorial and maritime disputes,” reads a new piece that is part of a collection on disputes in Southeast Asia beyond the South China Sea published by the multistakeholder Blue Security Project. The piece looks at disputes between Indonesia and Malaysia and Malaysia and the Philippines in designated areas of what is termed the Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea (see above map), and argues that while differences have yet to escalate into open conflict, they remain a source of friction that is a barrier for developing valuable marine resources such as offshore petroleum and a potential flashpoint for future fishery disputes as overexploitation exacerbates stresses. The full series also includes other cases such as the Malacca Straits and the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

“Some Philippine participants suggested that the U.S.-Philippine alliance should adopt some of the institutional developments in the U.S.-Japan alliance to better operationalize military plans in times of crisis,” notes a lessons learned section from a scenario-based exercise on U.S.-Philippines-Japan trilateral cooperation released by Pacific Forum. The recommendations suggested, following the scenario which included the harassment of Philippine vessels by China en route to Second Thomas Shoal, include increased clarity on operationalized defense guidelines, trilateral naval and coast guard exercises to cope with developments including a Taiwan scenario, and collaborating on the plight of Filipino workers in China, which could be utilized as a bargaining chip by Beijing to pressure Manila. The report, based on convening that occurred last December, comes amid increased U.S.-Japan-Philippine trilateral cooperation also being undertaken in practice.

“Asia is projected to see a reduction in GDP of 26%, trailing only the Middle East and Africa (27%). In fact, Southeast Asia fares even worse, with an expected hit of 37% -- by far the worst-affected region around the globe… four Southeast Asian nations – Myanmar, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand – are among the top 10 countries most affected by climate change in the past 20 years,” notes a report on corporate climate change action in Asia released by the World Economic Forum, Boston Consulting Group and SAP, that also details specific examples of the stakes for Southeast Asia (see the report graphic below for a visual sense, which draws on previous data from the Swiss Re Institute). It argues that while Southeast Asia is part of the story of Asia being at the heart of the climate challenge and opportunity, corporate action is currently inadequate and could benefit from a climate action framework that prioritizes taking immediate action; enabling transformation; and unlocking new growth. You can read the full report here.

What the EU’s First New Southeast Asia Space Partnership Really Means