New China Strategic Partnership with East Timor: Minding the Spillover Challenge

Plus key army chiefs meeting; reimagining supply chain development; Thailand-Cambodia summit and much more.

Greetings to new readers and welcome all to this edition of the weekly ASEAN Wonk BulletBrief! For this iteration, we are looking at:

Assessing the implications of the new China-East Timor comprehensive strategic partnership, which happened to take shape just as ASEAN Wonk was on the ground in Dili (Note to Readers: ASEAN Wonk was on the ground this week in East Timor as part of the latest regional swing through Southeast Asia – arguably the least visited country in the region. A few readers asked if we could share a little more about the new CSP. Most of the conversations we had on the ground were confidential and for a couple of separate projects, but we provide below in the latest WonkDive a snapshot of its strategic significance).

Mapping of regional developments including a key army chiefs meeting; China-Philippine South China tensions; a Cambodia-Thailand summit meeting and more;

Charting evolving trends such as on Southeast Asia’s stakes in supply chain reconfigurations; the energy transition as well as related issues;

Tracking and analysis of industry developments including a new e-commerce ban, the latest round of carbon pact hype and more;

And much more!

WonkCount: 1,771 words (~9 minutes reading time)

Army Chiefs Meet; China-Philippine South China Sea Tensions; Thailand-Cambodia Summit Spotlight & More

New China Strategic Partnership with East Timor: Minding the Spillover Challenge

Ground realities in East Timor suggest that the ongoing focus on the specifics of China’s new elevated partnership with Dili obscures the broader, longer-term need to mind what might be termed as the “spillover challenge” in ties, with implications for the broader Indo-Pacific region.

What’s Behind It

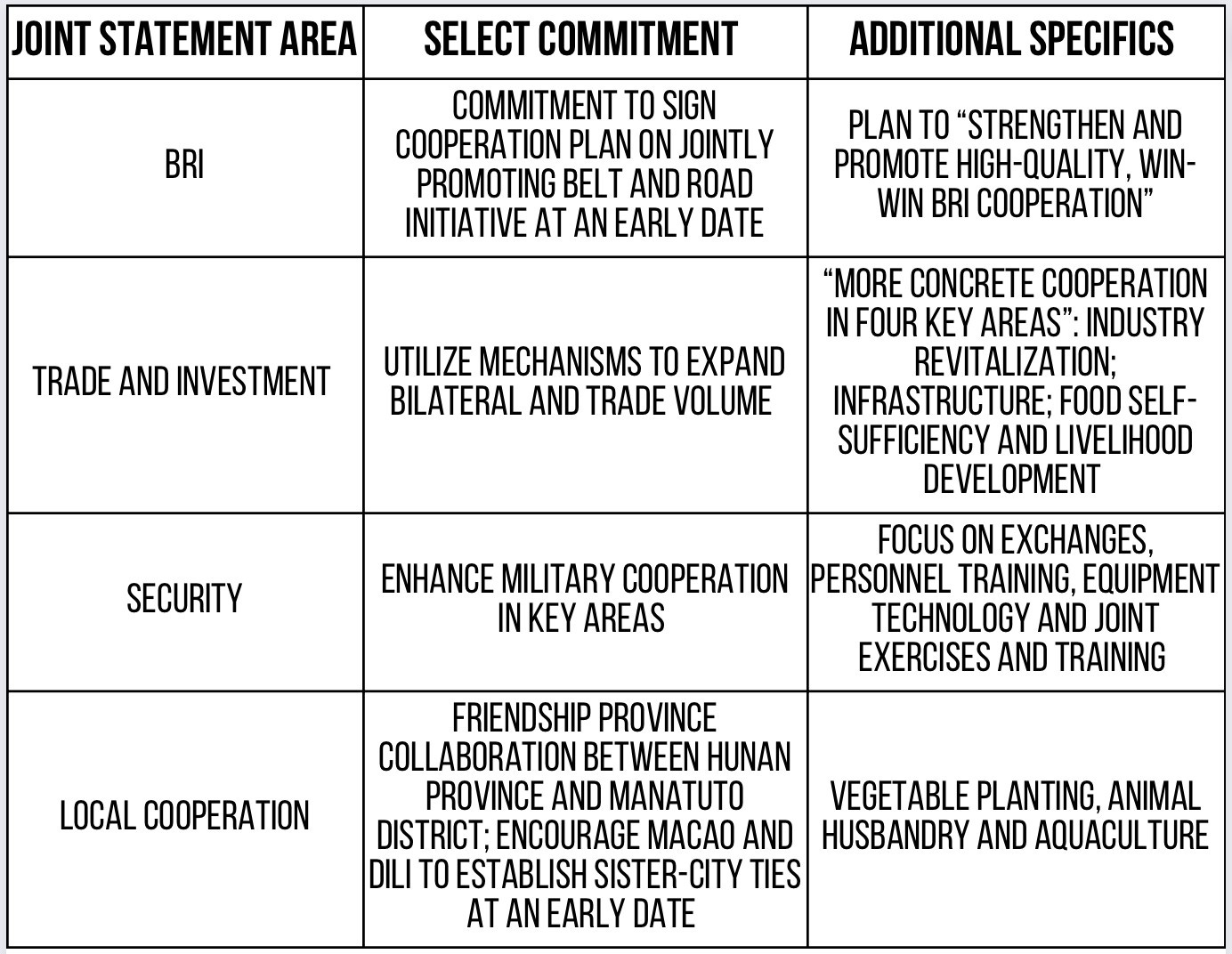

China and East Timor formally elevated their ties to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) on September 23. The partnership was announced during Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao’s visit to Hangzhou, where he was also attending the 19th Asian Games (see select areas set out in the joint statement below)1. Much of the focus of the partnership is on economics, but there is language on security collaboration and a link to broader strategic initatives like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Key CSP Joint Statement Areas and Specifics

The elevation is an early foreign policy marker for the new government following parliamentary elections in May earlier this year that saw a return to the premiership for independence hero Gusmao. While Southeast Asia’s youngest nation has defied the odds and successfully preserved its democracy and sovereignty since formalized independence in 2002, it remains among the region’s most underdeveloped nations, ranking 140th on the UN’s Human Development Index just below Laos and slightly ahead of Cambodia and Myanmar2. Economically, it has also struggled to diversify away from its traditional energy dependence, which accounts for the majority of its exports and growth3.

Why It Matters

The elevation to a CSP reflects China’s role within the mix of partners Dili considers key to achieving its national objectives. For all the focus on the geopolitical aspects of the partnership, those who have spent time in East Timor and are familiar with the country’s ground realities will note the link between areas mentioned in the CSP and the myriad manifestations of the country’s urgent development imperative (see select economic areas in the table below), from limited Internet and airline connectivity to the lack of nutrition — to take just one vivid example, nearly half of children under five are stunted4. There are also indicators of a more diversified presence of players in the country relative to a few years ago, including a growing role from fellow Southeast Asian countries like Singapore that could also be more of a part of Dili’s story as its admission into ASEAN takes shape following in-principle inclusion approved in 2022.

Economic Sectoral Initiatives in CSP Joint Statement

The partnership has also highlighted the spillover challenge inherent in some countries and their interactions with Beijing. Suggesting that East Timor’s leaders would blindly walk into some sort of China trap would seem to be at odds with the country’s history, where the very revolutionary figures leading the country today fought hard for independence, first achieved under Portugal and then regained after resistance against Indonesia’s subsequent invasion and occupation. At the same time, as we have in seen in other instances in Southeast Asia and in other regions like the Pacific, China has shown its ability to first make inroads in the economic domain that is receptive to partner priorities but then use that as leverage to gradually creep into strategic areas like communications and infrastructure, which in turn can spill over into the security realm, whether it be through periodic exercises, a civilian police presence or dual-use ports. “With China, we know nothing is really free,” one government source told ASEAN Wonk in Dili5.

Where It’s Headed

Looking ahead, the focus will be on the extent to which we will actually see early indicators of the partnership translating into tangible cooperation as well as potential indicators of the spillover challenge at play. Much of the international focus will be on more direct, visible and headline-grabbing defense manifestations of the spillover challenge, such as indicators of Chinese security presence or exercises that was present in the language of the CSP. President Jose Ramos-Horta, for his part, has unsurprisingly downplayed the likelihood of more direct spillover, noting that no explicit military cooperation was discussed as part of the CSP and that Australia will remain Dili’s main security partner6. Yet even if these do not materalize anytime soon, will be equally important to monitor some of the leading economic indicators, be it Ramos-Horta’s mention of a coming loan from China or extensions of maritime cooperation under the banner of fisheries collaboration.

In the longer term, the emphasis should also be on continuing to assess the ability of the country’s own actors to manage the opportunities and challenges that arise from closer ties to China, apart from the role of other external powers like Australia or the United States. While it is true that the proximity of East Timor to both Australia and Indonesia means that Dili will be cautious about how the sorts of arrangements it makes with China will play into calculations by its neighbors, the flip side of that is that there is also some limited room to leverage that to get more from its partners. Ultimately, the extent to which China is able to make inroads in countries like East Timor is contingent first and foremost on how various domestic parties negotiate agreements in the name or regime and/or national interests. Government and non-government actors within East Timor are not unaware of the costs inherent in some greater collaboration with Beijing, but these will be balanced alongside potential benefits and will take shape alongside broader longer-term developments including the gradual transition to a newer generation of leaders elected by one of Asia’s youngest populations. Dili’s dealings with other major powers will also factor into this, with a case in point being ongoing Greater Sunrise project talks.

The Great Supply Chain Remaking; Beyond a South China Sea Code of Conduct; Learning from Indonesia’s Energy Transition

“If they are to better manage economic security in view of new ethical governance practices, Southeast Asian states must play multiple, overlapping games beyond the geopolitical game that has dominated regional imaginations thus far,” argues a piece about Southeast Asia’s stakes in the ethical remaking of global supply chains featured over at Global Asia. The article examines several trends that have affected Southeast Asian states, including new industrial policies and environmental legislation. It is part of a collection of perspectives on middle powers in the Indo-Pacific region, which touches on issues like U.S.-China competition and regional institutions like ASEAN (link).

“Southeast Asian states could consider promoting, in parallel to the COC process, the development and negotiations of another instrument to manage all maritime engagements by all relevant parties in all Southeast Asian waters: a ‘Code of Conduct for Maritime Engagements in Southeast Asia’,” notes a new commentary over at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative on how to move beyond the code of conduct on the South China Sea (link).

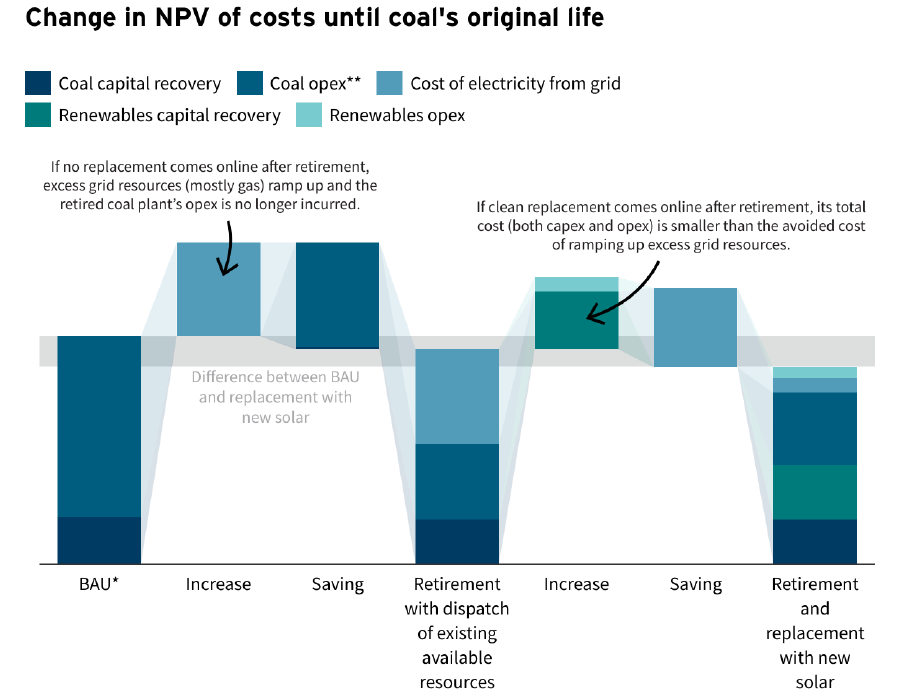

“[L]essons from Indonesia…are especially important in coal-dependent countries with high energy demand growth,” notes a new study by RMI on Indonesia’s coal transition amid the multi-billion dollar Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). The study, which leverages data from Indonesia’s state-owned utility PLN, finds that among other things, there is a need to move beyond only retiring coal plants to a broader view where retirement actions are linked to decarbonization of the broader grid, and that it is cheaper on a net present value basis to build entirely new solar power to cover the yearly generation of a coal plant than ramp up idle capacity on the grid (see figure below as an example) (link).